This is a series for resistance. For keeping the mind and spirit healthy in a time of great distress. I am an expert in nothing, a student in all. And I see around me now the triumphant inexpert, all of us set floundering in the wake. At our peril we declare ourselves experts. If we were experts, none of this would have happened. But we thought we knew ourselves, and look: See how the cup was filled with poison, every structure seeming strong shot through with cracks, crumbling at the dusted smell of distant storms.

Drink deeply of this draught: humility for the humbled. An admission that it – all of it – has not been nearly enough, that vaunted expertise. Something else, some thorough self-education is needed in the afterglow of a violence thought unfathomable. And so, first, I educate myself.

Who goes with me? Who will serve as guide, my Virgil in the tolgy wood?

Well.

It’s Papa Haydn. I choose him. I might as well say why. First, there’s enough of him to last. Even if I can’t sustain this impulse, he can and did.

I was in his house just off the Mariahilfer Straße and saw things I’ll never forget. I saw Haydn’s workhorse of a keyboard, off in a closet to the side. And the pockmarked courtyard. Did I see the spot where one of Napoleon’s cannonballs had fallen, frightening the “members of Haydn’s entourage…out of their wits,” the house shaking “as in an earthquake,” as Karl Geiringer put it? [1] And the wax bust of the man, looking the talk of town in tatty Tussaud treatment, crayon Paul McCartney in a powdered wig.

But it’s the keyboard – little sacred thing – that I hold closest when I remember that chilly Viennese January day. What would he have worked on there with those nimble fingers, in that very space, over those very keys? I remember no sound in that room, but could that be true? Do I misremember? Was the universe really good enough to hand me such irony: a profound silence where music was born, again and again? Can respect take the shape of irony? Is that a humor Haydn would have appreciated?

I’m afraid I love him, Papa Haydn, and have for a long time. I can’t help myself. I’m not alone, of course, but I confess it, nonetheless, admit myself to the ranks. And so this act of resistance is an act born out of love. Many things will emerge, inevitably. All the other justifications. A panoply of tangents. The occasional burst of trenchant analysis, and much else I in my manifold mortal limitations perceive as trenchant. That’s fine. I’m not worried, am not intimidated into inaction. Resistance is a process, and only through the process can I achieve the quality of resistance I seek.

Some entries will be like this, I think. Mostly thinking “out loud,” through written words, with Haydn informing the proceedings. Others I anticipate will be immediately and wholly about the music. From this side of the journey it’s hard to see how the road twists and bends.

But here we are at the beginning, so I feel overjoyed (and obligated) to say something about H. I:1, the Symphony No. 1 in D Major. There’s no need to be exhaustive, he tells himself, and, in keeping with the spirit of Sound Trove, there will always be the other impulse, which is to write about recorded sound and not only about the score that Haydn penned in 1759 or maybe a bit earlier.

Recordings, then. It’s quite thrilling to search for performances of Haydn’s First on YouTube. This compared with the set of LPs in the listening library, Antal Dorati and the Philharmonia Hungarica from over 50 years ago. Nothing wrong with that per se, but there’s something to be said for beautifully recorded sound, spicily played and smartly cut on video. Here, for example, is the Frankfurt Radio Symphony under Richard Egarr, conducting from the harpsichord, and take a few minutes to enjoy the playfulness of his improvised link between the first and second movement.

Thanks to the video, you can see how much the violins enjoy Egarr teasing them. At least I think they’re enjoying it. I don’t perceive any of them resenting Egarr his musical license. Are they thinking of PH himself, wondering if this is the sort of thing that would have been done in 1759 chez Count Morzin? [2] Or is it just a moment of joy beyond words, musical joy?

Other YouTube offerings present wonderful ideas less satisfyingly executed, like the one performed at Schloss Esterházy by Il Giardino Armonico under Giovanni Antonini, the conductor on his podium and all the strings standing, the camera jumping from shot to shot, trying to be a Marvel film, while the performance itself strolls through the music with too aristocratic poise, all elegance without misbehavior. (The through line I found is the hall itself.)

But here’s our old stalwart, Dorati, and… ye gods! The harpsichord is so quiet – is it even there in the first movement? – that Haydn sounds closer to Beethoven than he ever does these days, even in a work from 1759(?). (Some generous soul has put all 425 movements from the Dorati set on a YouTube playlist, so if you let it play from the first movement below, you’ll hear the second and third.)

It’s at this point that I ask myself, having written little bits over a few days, whether there’s any continuity of tone to be had in this long entry, whether that matters, and whether there are things I must say before leaving H I:1 behind. (What, forever?! I refuse!)

I won’t worry about continuity too much, since I’m warming up, but yes, there are things I simply have to say. No, not necessarily those things that a well-mannered musicologist is meant to say. Things about how this is a symphony on the three-movement Italian design, missing a minuet, about the nature of the first movement’s development-light sonata form, the absence of winds in the Andante (“following the local tradition”), etc. Reading through Landon’s comments on the work gives a sense of much of that, though he spends a surprising amount of time extolling the virtues of Haydn 104. [3] Why talk about Haydn 1 through Haydn 104? “In my end is my beginning,” or maybe “you ain’t seen nothing yet.” T. S. Eliot or Bachman-Turner Overdrive, as you prefer.

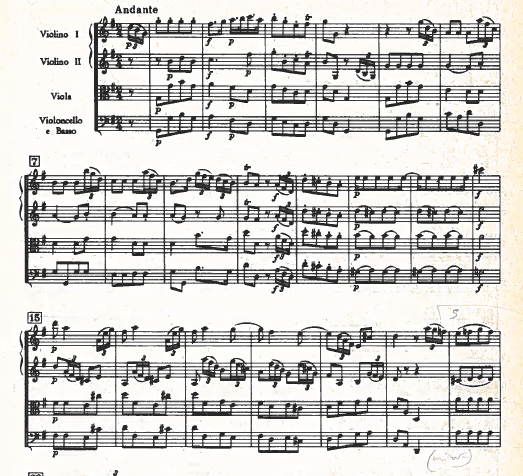

Still, I’ll choose one little thing that I dearly love as a downpayment toward lengthier musical commentary in future entries. Here it is: my one thing. In that lovely little second movement, there is a cessation of timekeeping that I find arresting. Here’s the score so you can see what I mean.

The rhythm has been so pert, the melody spiked with staccatos, until the syncopated figure at m. 12 eases us toward suspension of motion, and then… the clock stops ticking! A measure where everyone plays a half note, marked forte. What you do with that in performance is an entirely different matter. Generally performers play it as a sort of swell of an accent with a quick decay, probably because Haydn marks the measure right after it piano. It’s this sort of quirkiness, an ability to surprise and to reward the ear attuned to surprises, that keeps us coming back. We are ready, Papa Haydn. Lead on.

[1] Karl Geirigner, Haydn: A Creative Life in Music, rev. (Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1968), 205.

[2] H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: The Early Years, 1732–1765 (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1980): 235. [3] Ibid, 283–5.

[3] Ibid, 283–5.