Where does it come from, counterpoint? I don’t mean historically – I have a fair sense of that, having studied such things for some time. What I really mean is, where does the compulsion to create learned counterpoint come from in the mind of the composer? It doesn’t have to come from one place, does it?

The calculated use of counterpoint, in a dramatic context, to connote struggle, disruption, strife, is worlds away from the use of counterpoint in a genre where counterpoint is simply the expectation. I can put names to it, if that helps: for the dramatic, the use of fugato in the development section of Beethoven’s Third Symphony – an easy example, but familiar; for the expected, a Kyrie in a Mass setting by Palestrina. Unsafe versus safe counterpoint, we might say; order threatening to split apart versus the great multifarious multiplicity of things made into a harmonious whole. In other words, diametrically opposed readings prompted by the same phenomenon.

I suppose the dramatic use of learned counterpoint, to signify contention, must have been a gift from Bach and Handel. I’m thinking of the cantatas and oratorios, respectively; the Passions, as well. The claim couldn’t really be made for Schütz, could it? Stick a pin in it – something to explore on another day. That is, I can’t rule out with absolute certainty the possibility that Schütz, that magnificent musical rhetorician, used a choral fugue, say, to convey some conflict in the text. I welcome clarification from some benevolent Schützian who happens this way.

Eventually, Haydn will give us some of this – counterpoint signaling contention – but in his Third Symphony, counterpoint is something else. Play, perhaps. Maybe that’s a Haydn ca. 1759/60 way of “turning the multiplicity of things into a harmonious whole,” but it feels more like a bit of youthful exuberance, tinged by the flexing of mental muscle. For who in 1759 would have written a symphony so committed to contrapuntal technique? Was there one other person who would have, who could have, besides our young Haydn?

I’ll make three points: two as quickly as possible and one at a bit more length.

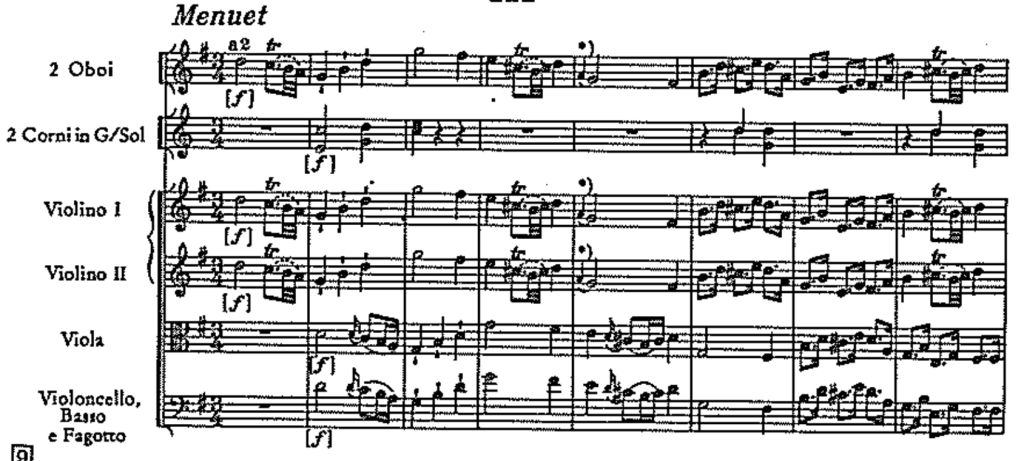

First, the two quick things. Movements one and four are bound, yes bound, together by their first themes, each clearly designed for contrapuntal treatment by virtue of their first four notes, with each note filling up a measure to establish harmonic clarity and open up space for the activity of a countermelody. (It’s easier to see it than to read about it, so here you go.)

What is this, Papa Haydn? Cyclicity? Can we really accuse you of creating a “themed” symphony in 1759, with learned counterpoint itself as the “subject,” ha-ha? Would you have thought of it, and, if so, would anyone have heard you? Well of course he would have thought of it, because eventually he does think of it, and how can anyone claim that the grand arrival of the cyclic symphony in Beethoven’s Fifth is sui generis when Haydn and Mozart are teasing at the concept decades before. Still…1759, Haydn? What historical precocity! Once more, we lesser mortals bow and scrape.

I know I promised to be brief with the first two points, but I can’t resist noting the connection between what Haydn does in his fourth movement and what Mozart would do in the Finale of the Jupiter Symphony (1788), that juggernaut of symphonic contrapuntality, so grand a conception to those who heard it that it took on the name of a god. To get right to it, Mozart’s Finale also opens with a four-note, note-to-the-measure theme, primed to fulfill a contrapuntal destiny. Beyond this, there’s no comparison between Haydn’s Third and Mozart’s K. 551. One is an early work in a genre that had yet to attain much significance; the other is a summative work, harbinger of Beethoven, the last of the numbered Mozart symphonies in a genre that was quickly becoming, to the late Enlightenment, what the Mass had been for Palestrina: a place to put your best work. That Haydn was going to help usher the genre on to its exalted plane is the stuff of every music history class, but in that well-worn narrative, it’s easy to forget about early intimations like H. I:3.

Now the third point, and this one takes the cake.

If you’re familiar with Haydn’s First and Second Symphonies, you’ll know that the Third is the earliest, in the numbering system we now use, that has four movements instead of the Italian three. It gains a minuet (or “menuet,” as Haydn spelled it) in the third position. All the formal things that we know about the minuet – that it’s a paired dance with a trio, that each of the dances (minuet and trio) will be its own rounded binary form, that the convention is to play the reprise of the minuet without the repeats – are as true here, in 1759/60, as they will be when Haydn pens his last symphony. And here, in the first minuet we stumble upon while tripping through Papa H.’s symphonic oeuvre, we encounter another eternal verity, this one belonging to Haydn alone. It’s a principle, I suppose, and easily expressed: No boring dances, please. Is it important to say it? Yes, it is, so I might as well get it out of the way. Haydn’s minuets are better than Mozart’s. There. Band-aid ripped off. Let’s not dwell on it more for the moment, though perhaps in another entry I’ll have the wherewithal to step up to the plate. But for now…

Check it.

The opening of this diminutive dance, this “throwaway” minuet, is a canon. (Danced any canons lately?) And this means, of course, that three of the movements of this four-movement symphony are colored by learned counterpoint.

It gets even better. The canon in the first section (A) proceeds as one might expect, with the high voices (violins, oboes) serving as leader and the low voices (violas, cellos, basses, bassoons) answering after a measure, and this relationship continues in the second section (B). But when the reprise of the A section (A’) begins, the relationship has been reversed: now the lower voices start the canon, with the upper voices answering after a measure.

In other words, and to risk a bit of contrapuntalese, Haydn has made an invertible canon: the answer fits, harmonically, above or below the leader, a bit of contrapuntal magic that one might look for in an Art of Fugue but that comes as a complete – and delightful, even funny – surprise in a modest little dance. In the tension between genre, thematic material, and working of that material, Haydn introduces himself as an ironist.

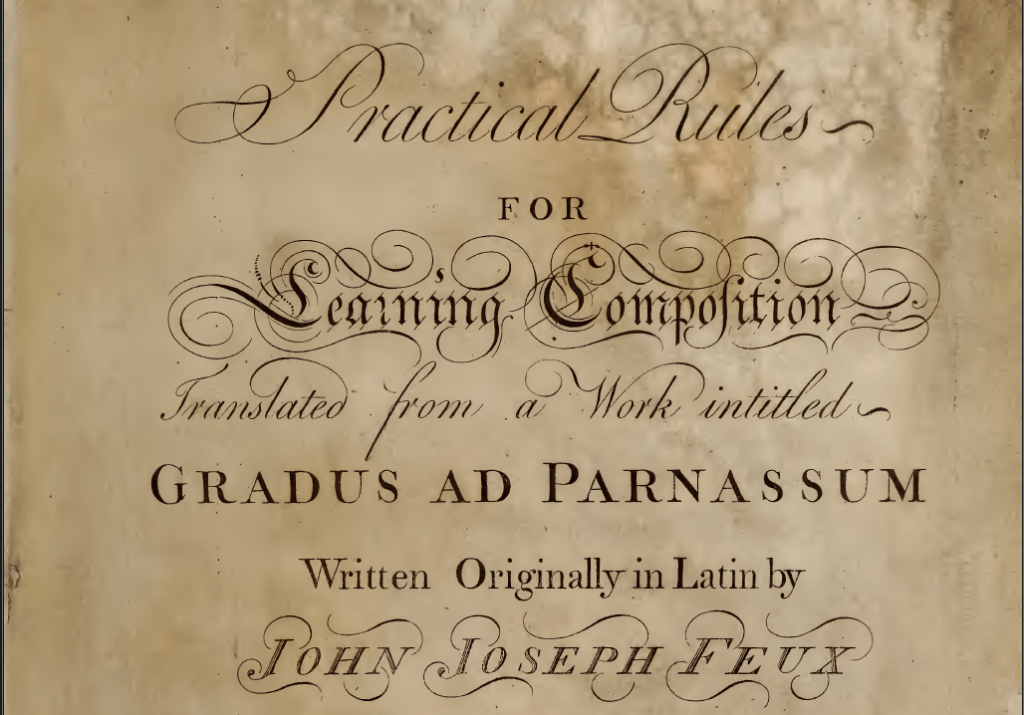

There in his garret apartment, not long after his ignoble departure from St. Stephen’s, wretchedly poor, poring over a copy of Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum, perhaps it occurred to Haydn: from even the most modest of origins, wonders and marvels might emerge. [1]

[1] As Geiringer writes about Haydn’s first room of his own: “It was a garret, partitioned off from a larger room in the old Michaelerhaus near Vienna’s ancient Romanesque Church of St Michael.” While there, “He devoured Joseph Fux’s famous Gradus ad Parnassum, Johann Mattheson’s Der vollkommene Kapellmeister, and David Kellner’s Unterricht im Generalbass. The copies he used have been preserved, and their numerous annotations reveal the passion with which young Haydn threw himself into the study of these subjects.” Karl Geirigner, Haydn: A Creative Life in Music, rev. (Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1968), 31.