First impressions matter.

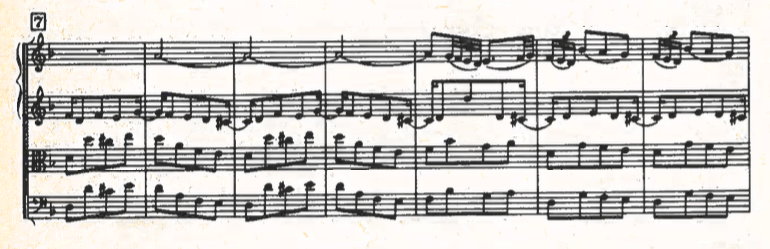

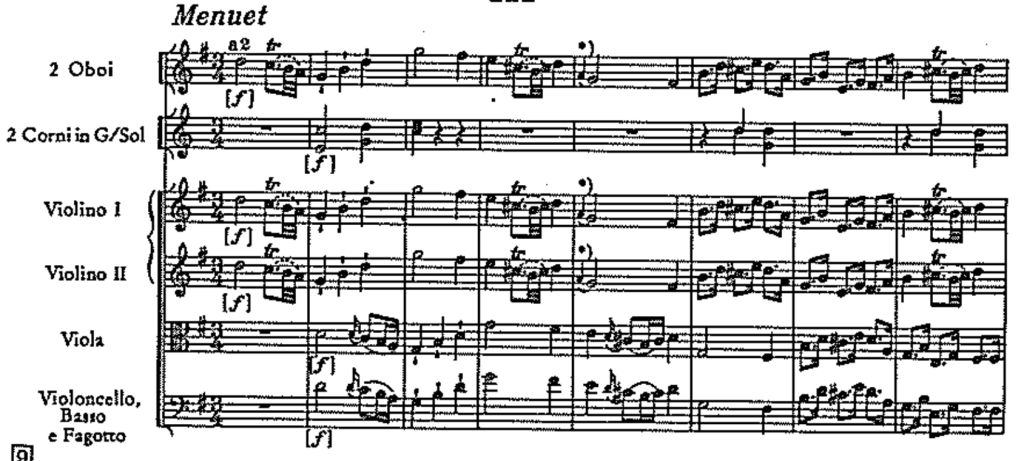

Seriously. Who would ask this of a pair of hornists in 1760?

But you should also really consider the (unhinged?) Trio from the third movement. Observe, please, the total absence of any safety net, the radical exposure of the hornists. Were they quaking in their liveries, one wonders? Forget the mannered surety of “hunting horn figures” – these fellas are stalking the jabberwock with laser cannons. Or maybe it’s more like Die schöne Müllerin meets Hair.

This can’t be normal, can it? My initial impression, at least, was that it can’t be. In other words, not the kind of horn writing that seemed tricky in a genteel, doily-dappled past but would gradually become old hat to your average monster hornist. This horn writing sounds like it would remain treacherous. As evidence I note that YouTube offers no live performance, as far as I can tell. And had there been a live performance, just what facial expression might that pair of hornists have worn the bar before their entrance… Grim resolve? Silent appeal to the divine? Rabid-dog excitement? [1]

But then I turned to someone who, you know, actually plays and researches natural horn, fellow San Antonian Dr. Drew Stephen, who explained that the demands Haydn puts on his hornists in the Fifth Symphony are “a little unusual, especially for an early symphony,” but not exceptional. [2] Haydn’s writing in the Fifth simply expects that the hornists would have been comfortable playing in the clarino register, that’s all. Not worlds apart, I suppose, from the bracing effect of clarino trumpet in Brandenburg No. 2. To us lesser mortals it might seem a miracle, but it was once someone’s day job.

My analytical process is always to listen with the score first and to develop my thoughts a bit before turning to other writers, etc. – put it down to anxiety of influence, which is to say that I suspect my own unusual perspective will emerge with greater clarity in the absence of other people’s ideas – and that’s what I did this time. But then, after the eye-popping, spine-tingliness of this horn experience, I turned to my trusty copy of Chronicle and Works, and read this from Landon: “Hardly have the strings begun [in the first movement]…than the solo horns enter with a passage of greatest difficulty [italics added].” And this about the Trio: “This [folk-like] atmosphere is…enhanced by the solo horns (again reaching sounding a’’) and solo oboes.” [3] Yes, Landon half-dresses it up in regalia, but you know what he’s saying, right? Psycho horns. But, pace Landon and my own first impression – sometimes it’s best to trust the experts!

For what it’s worth, the second and fourth movements don’t make such demands. At first, I wondered if Haydn felt he could only get away with asking such things of his hornists if he gave them a smoke break every other movement. That’s what the composer in me might do on a friendly sort of day. And there is a bit of an interrogation atmosphere in this symphony, with alternating bad cop and good cop movements. But here, too, the good Dr. Stephen has assured me that no recovery time would have been needed. “Once you get in that [clarino] groove, it is not particularly tiring.” So maybe Haydn was even being overly cautious by “underwriting” in the second and fourth movements, the opposite of my initial impression. Still, I console myself by observing, in Drew Stephen’s kindly compiled list of clarino horn ranges in early Haydn symphonies, that Papa H. only ever exceeded the (sounding) highest note of the Fifth Symphony once, and then by a half step. So H. I:5 is high, OK? It is! It’s just maybe clarino high instead of psycho high.

Of course I’m being a tad bit silly. All the above might give you the impression that the hornists were bad and that Haydn was punishing them by writing such high parts, but the opposite is more likely. I would guess that Haydn met a couple of hornists – at Count Morzin’s, or perhaps a couple of guest artists? – who were so phenomenally good, so completely rock-solid reliable, that he wrote the symphony with them in mind so they could show off. And, when they performed it? Doubtless the Countess Wilhelmine would have fluttered her fan most fervently at such ferocious horn shredding.

I mentioned that the second and fourth movements don’t have the same kind of “extreme” clarino horn writing, and this means that Haydn’s Fifth is a four-movement symphony. This does not mean, however, that the four movements follow the (yet-to-calcify) classic Haydn design. It’s something quite different, and this adds to the atmosphere of strangeness in a few ways.

Qu’est-ce que c’est, you ask?

The well-trained musicologist in me did, I admit, recognize in Haydn’s Fifth the outlines of a sonata da chiesa, that by-then old-fashioned four-movement genre with a slow-fast-slow-fast (usually?) design. Oh, you know, the sort of thing Corelli wrote. I wasn’t surprised, therefore, on cracking open my Chronicle and Works to see Landon mention the sonata da chiesa in his comments: “Here is another work in the sonata da chiesa form, opening with an entire Adagio…” [4]

That’s fine up to a point, but the curious thing is that the opening Adagio of H. I:5 is nothing like the kind of slow movement that Corelli would have written. We can easily see the outlines of sonata form in it, albeit with underdeveloped secondary material. Further, instead of giving us a slow third movement à la sonata da chiesa, he gives us a minuet-trio, as we expect in what will become Haydn’s normative symphonic plan. In other words, H. I:5 is a work sui generis and in generic transition, tugging between the Italianate three-movement symphony, the older sonata da chiesa, and the Haydn four-movement design of the future.

Landon drops us another nugget of knowledge in his commentary, and this one gave me an opportunity to learn something new. “Here, in No. 5, we have an interesting example of the divertimento-cassatio technique being applied to such a solemn, slow movement: hardly have the strings begun by themselves (leading us to believe that this is a typical wind-less slow movement) than the solo horns enter…” [5] And you probably remember the rest, or, if you don’t, you can browse the top of this entry. Ye olde “divertimento-cassatio technique,” eh? I had to do some homework for this one – SHOCK! – and strolled for a bit in a budding Grove (Music Online) to get a better handle on “the cassation.”

And?

I’m afraid it’s complicated, as so many generic designations are in the 17th and 18th centuries. What to share? Well, after some wrangling about etymology, the Grove entry writers land on the German Grassaten or Gassaten as the origin of the term cassation, connected to a saying current among mid-18th-century musicians that meant “to perform in the streets” (“gassatim gehen”). [6] So it seems that a cassation has to do with playing outside, which suggests (loud) wind instruments, which in turn explains Landon’s comment about the first movement of the Fifth Symphony, where we’re tricked by the instrumentation and tempo of the opening to expect inside music (strings sawing sweetly) only to be jolted awake by outside music: horns, just about as high as they could go.

Don’t miss this, though! After all is said and done, this opening movement – whatever alchemical amalgam of sonata form and sonata da chiesa and cassation – is an Adagio, and that makes Haydn’s Fifth the first of the numbered symphonies where the slow movement is the first thing we hear and also the first in which a slow movement has wind instruments at all. The wildness of the horn writing, if that’s what it is, is therefore of a piece with the wildness of Haydn’s formal invention.

And that makes Haydn’s Fifth fa-fa-fa-fa, fa-fa-fa-fa far better, I’d say, than the AI-generated mashup of David Byrne+Haydn playing the horn (?) that you will now possibly not be able to unsee.

[1] When do I get paid?

[2] Many thanks to Dr. J. Drew Stephen, Associate Professor of Music History at the University of Texas at San Antonio for an enlightening email exchange about clarino writing, especially in early Haydn! You can hear his introduction to natural horn on his UTSA bio page: https://colfa.utsa.edu/faculty/profiles/stephen-john.html

[3] H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works, The Early Years, 1732–1765 (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1980): 292.

[4] Idem.

[5] Idem.

[6] Hubert Unverricht, rev. Cliff Eisen, “Cassation,” in Grove Music Online, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic.

This led me to a 5-disc compilation, Ovation: Volume 2, which does indeed feature a disc of R. Murray Schafer’s music that includes his first concerto, written in 1954 for harpsichord and eight wind instruments. But that’s for some other time. This time I couldn’t resist the first disc in the set, featuring an assortment of pieces by another Canadian, Violet Archer (1913-2000), covering an almost 40-year span, from the Sonata for Flute, Clarinet and Piano of 1944 to the finale from the Sonata for Unaccompanied Cello of 1981.

This led me to a 5-disc compilation, Ovation: Volume 2, which does indeed feature a disc of R. Murray Schafer’s music that includes his first concerto, written in 1954 for harpsichord and eight wind instruments. But that’s for some other time. This time I couldn’t resist the first disc in the set, featuring an assortment of pieces by another Canadian, Violet Archer (1913-2000), covering an almost 40-year span, from the Sonata for Flute, Clarinet and Piano of 1944 to the finale from the Sonata for Unaccompanied Cello of 1981. Not that Archer could have known that in 1944, which begs the question: What’s it doing in there, besides parading around its insouciant self? A little searching revealed that Sobre las olas supposedly had a long association with (fun)fairs in the United States, in part because it was a tune available on Wurlitzer fairground organs. If that’s where Archer got the idea to use the tune – she was an organist, after all? – then its use seems of a piece with the “classic” neoclassical aesthetic set forth by Cocteau in Le coq et l’arlequin, bringing fairs and circuses and machines into the concert hall.

Not that Archer could have known that in 1944, which begs the question: What’s it doing in there, besides parading around its insouciant self? A little searching revealed that Sobre las olas supposedly had a long association with (fun)fairs in the United States, in part because it was a tune available on Wurlitzer fairground organs. If that’s where Archer got the idea to use the tune – she was an organist, after all? – then its use seems of a piece with the “classic” neoclassical aesthetic set forth by Cocteau in Le coq et l’arlequin, bringing fairs and circuses and machines into the concert hall. Elsewhere in the notes the writer says that Archer was composer in residence at “Texas State University” before moving on to the University of Oklahoma; I can only imagine that NTSU/UNT is what was meant, and indeed there’s a brief bio of Archer on UNT’s website on a

Elsewhere in the notes the writer says that Archer was composer in residence at “Texas State University” before moving on to the University of Oklahoma; I can only imagine that NTSU/UNT is what was meant, and indeed there’s a brief bio of Archer on UNT’s website on a  (Picture eight instrumentalists with headphones, each hearing a different clicktrack, with everything routed through a massive central mixing board, wires strewn all over stage.) The piece itself was commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and in writing it Austin derived musical phenomena from maps of, yes, sections of the Canadian coastline. As a student I heard an anecdote about the piece where John Cage, Austin’s longtime friend, “seemed enthralled by the piece, and after the performance very enthusiastically said, ‘Larry, it was beautiful; I didn’t understand it.’” [1] I’ve often told that anecdote as a way of illustrating Cage’s aesthetic preference for unknowability, but just this week, through my encounter with the music of Violet Archer, Austin’s teacher, the piece has come to mean something more to me.

(Picture eight instrumentalists with headphones, each hearing a different clicktrack, with everything routed through a massive central mixing board, wires strewn all over stage.) The piece itself was commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and in writing it Austin derived musical phenomena from maps of, yes, sections of the Canadian coastline. As a student I heard an anecdote about the piece where John Cage, Austin’s longtime friend, “seemed enthralled by the piece, and after the performance very enthusiastically said, ‘Larry, it was beautiful; I didn’t understand it.’” [1] I’ve often told that anecdote as a way of illustrating Cage’s aesthetic preference for unknowability, but just this week, through my encounter with the music of Violet Archer, Austin’s teacher, the piece has come to mean something more to me.

Honegger’s Rugby, a piece inspired by that sport, would seem to represent an unusual phenomenon in art music. My search to find similar pieces has revealed that there are not many that relate directly to a sport or a game. (I welcome readers to add to my initial list!) Stravinsky wrote Jeu de cartes, for example, which of course deals (no pun intended) with a card game. Honegger may have been inspired by Debussy, whose Jeux features an attempt to connect musical rhythm with a bouncing tennis ball. However, Jeux is not directly inspired by the game of tennis. That most eccentric French composer, Erik Satie, did write Sports et Divertissements for piano solo, but the only actual sports subjects in the work are tennis and golf (unless you think Satie thought of yachting and fishing as sports). Bohuslav Martinů composed Half-Time, inspired by football (soccer). (Bateman 2015) I am not sure whether Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1908) should be counted as another example, since it’s mostly about watching the game (and eating at it), but even if it is, there are not that many popular songs that turn sports into music.

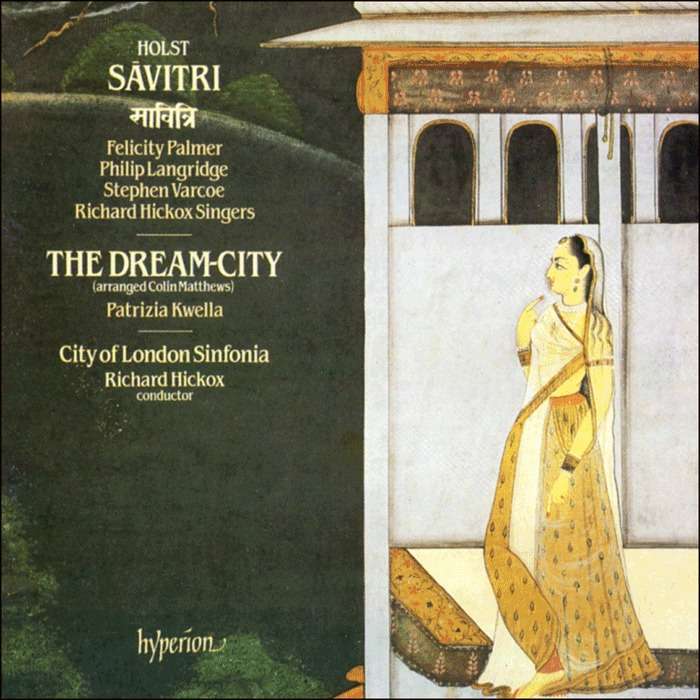

Honegger’s Rugby, a piece inspired by that sport, would seem to represent an unusual phenomenon in art music. My search to find similar pieces has revealed that there are not many that relate directly to a sport or a game. (I welcome readers to add to my initial list!) Stravinsky wrote Jeu de cartes, for example, which of course deals (no pun intended) with a card game. Honegger may have been inspired by Debussy, whose Jeux features an attempt to connect musical rhythm with a bouncing tennis ball. However, Jeux is not directly inspired by the game of tennis. That most eccentric French composer, Erik Satie, did write Sports et Divertissements for piano solo, but the only actual sports subjects in the work are tennis and golf (unless you think Satie thought of yachting and fishing as sports). Bohuslav Martinů composed Half-Time, inspired by football (soccer). (Bateman 2015) I am not sure whether Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1908) should be counted as another example, since it’s mostly about watching the game (and eating at it), but even if it is, there are not that many popular songs that turn sports into music. But the record I pulled off the shelf this week was not The Planets, but Holst’s Sāvitri (1908), a stunning one-act opera clocking in at about 30 minutes, with a B-side that I’d never heard: The Dream-City, a ten-song cycle that composer-conductor

But the record I pulled off the shelf this week was not The Planets, but Holst’s Sāvitri (1908), a stunning one-act opera clocking in at about 30 minutes, with a B-side that I’d never heard: The Dream-City, a ten-song cycle that composer-conductor  Another week, another ‘80s movie reference. Behold, I bring you: Beetlejuice (1988). Granted, the weird nightmare landscapes that Michael Keaton’s poltergeist-purveying title character slinks through in Tim Burton’s film are a far cry from the wisps of dreams in Humbert Wolfe’s poems. But something does tie together that bizarre film, Wolfe’s poetry, Holst’s settings, and Matthews’s orchestration: the strangeness of our fantasies about death.

Another week, another ‘80s movie reference. Behold, I bring you: Beetlejuice (1988). Granted, the weird nightmare landscapes that Michael Keaton’s poltergeist-purveying title character slinks through in Tim Burton’s film are a far cry from the wisps of dreams in Humbert Wolfe’s poems. But something does tie together that bizarre film, Wolfe’s poetry, Holst’s settings, and Matthews’s orchestration: the strangeness of our fantasies about death. This science-fiction-like vision of death—which reminds me of the terrifying frozen world of the White Witch’s home planet in C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew (1955)—becomes a marvel in Matthews’s rendering. He has forged a sonic Betelgeuse in the environment of his orchestration, with sly references to Mahler’s

This science-fiction-like vision of death—which reminds me of the terrifying frozen world of the White Witch’s home planet in C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew (1955)—becomes a marvel in Matthews’s rendering. He has forged a sonic Betelgeuse in the environment of his orchestration, with sly references to Mahler’s  Death sings the opening section alone, without orchestral accompaniment, which might initially suggest Wagner’s strategy at the beginning of Act I of Tristan und Isolde, but in Holst there’s no prelude to set up the emptiness of the opening song. And then, magic! Sāvitri joins Death in an unaccompanied duet and reveals that his song has been running through her mind. So the first character we hear is actually the thought of another character. The stark tension between the two vocal parts seems to prophecy Peter and Ellen’s bitonal duet in Britten’s Peter Grimes, which is similarly unmoored from orchestral accompaniment. Composer-scholar Raymond Head claims that Sāvitri features Holst’s first use of bitonality (“Holst and India (III)” Tempo 166 [September 1988]: 37), and given that Britten acknowledged his debt to Holst’s harmonic thinking, the Sāvitri-Grimes link seems intriguing.

Death sings the opening section alone, without orchestral accompaniment, which might initially suggest Wagner’s strategy at the beginning of Act I of Tristan und Isolde, but in Holst there’s no prelude to set up the emptiness of the opening song. And then, magic! Sāvitri joins Death in an unaccompanied duet and reveals that his song has been running through her mind. So the first character we hear is actually the thought of another character. The stark tension between the two vocal parts seems to prophecy Peter and Ellen’s bitonal duet in Britten’s Peter Grimes, which is similarly unmoored from orchestral accompaniment. Composer-scholar Raymond Head claims that Sāvitri features Holst’s first use of bitonality (“Holst and India (III)” Tempo 166 [September 1988]: 37), and given that Britten acknowledged his debt to Holst’s harmonic thinking, the Sāvitri-Grimes link seems intriguing. Just how deeply the connection between Xmas and the ultimate space opera, exemplified by an ever-growing corpus of Christmas Yoda memes, has embedded itself in the collective consciousness is difficult to say, but it’s clear that Disney grasps it. Of course they trot out a new Star Wars movie every Christmas for those of us who woke up one CRT-blasted, C-3PO-cereal-sated morning to our very own AT-AT. With extra pack of D batteries. They know what we want for Christmas.

Just how deeply the connection between Xmas and the ultimate space opera, exemplified by an ever-growing corpus of Christmas Yoda memes, has embedded itself in the collective consciousness is difficult to say, but it’s clear that Disney grasps it. Of course they trot out a new Star Wars movie every Christmas for those of us who woke up one CRT-blasted, C-3PO-cereal-sated morning to our very own AT-AT. With extra pack of D batteries. They know what we want for Christmas.

(How did this little piece of magic happen? Did John Williams hear Anthony Daniels’s scream and think, “Hm, the brass need to do something like that. I’ll write a screaming brass line. C-3PO screams, the brass scream, we all scream. . .for asteroid fields.”) A fraught favorite is the truly beautiful “Love Theme,” which finally gets the orchestral treatment it deserves in the closing scene of the film, as Luke and Leia, his arm around her, stand at the window on the medical frigate, looking out over the sweep of the whole galaxy. Right, so the only time we have the “Love Theme” as we’ve longed for it, it’s for. . .sibling embrace. Granted, they (and we) aren’t supposed to know this yet. But does this use of the “love theme” inject an intentional dose of ambiguity about the Luke/Leia relationship into the saga? Like Harry and Hermione dancing in the tent in The Deathly Hallows? Like Siegmund and Sieglinde in the first act of Die Walküre before the “reveal”? I’m pretty sure that the younger me just heard this moment as the uncomplicated and entirely sufficient love of all things Star Wars. Living in the nexus for a few decades has a way of complicating things.

(How did this little piece of magic happen? Did John Williams hear Anthony Daniels’s scream and think, “Hm, the brass need to do something like that. I’ll write a screaming brass line. C-3PO screams, the brass scream, we all scream. . .for asteroid fields.”) A fraught favorite is the truly beautiful “Love Theme,” which finally gets the orchestral treatment it deserves in the closing scene of the film, as Luke and Leia, his arm around her, stand at the window on the medical frigate, looking out over the sweep of the whole galaxy. Right, so the only time we have the “Love Theme” as we’ve longed for it, it’s for. . .sibling embrace. Granted, they (and we) aren’t supposed to know this yet. But does this use of the “love theme” inject an intentional dose of ambiguity about the Luke/Leia relationship into the saga? Like Harry and Hermione dancing in the tent in The Deathly Hallows? Like Siegmund and Sieglinde in the first act of Die Walküre before the “reveal”? I’m pretty sure that the younger me just heard this moment as the uncomplicated and entirely sufficient love of all things Star Wars. Living in the nexus for a few decades has a way of complicating things. This reminds me of a recent conversation I had with Bill Gokelman (Chair of the UIW Department of Music), who had played the piano part for some excerpts from Star Wars (as performed by the San Antonio Symphony) some years ago and was stunned by the demands placed on the pianist. With so much piano activity, why is there so little evidence of it in the film? Why hide the piano? Is it too human a sound, suggestive of real people playing real instruments? It’s certainly a sound that never emerges from Wagner’s pit. Or maybe the timbre itself comes across as too American neoclassical? Whatever the filmmakers might have thought when dusting the piano under the sonic rug, when I hear John Williams’s “frightful invention” on the OST, the reference that leaps to mind is George Antheil’s

This reminds me of a recent conversation I had with Bill Gokelman (Chair of the UIW Department of Music), who had played the piano part for some excerpts from Star Wars (as performed by the San Antonio Symphony) some years ago and was stunned by the demands placed on the pianist. With so much piano activity, why is there so little evidence of it in the film? Why hide the piano? Is it too human a sound, suggestive of real people playing real instruments? It’s certainly a sound that never emerges from Wagner’s pit. Or maybe the timbre itself comes across as too American neoclassical? Whatever the filmmakers might have thought when dusting the piano under the sonic rug, when I hear John Williams’s “frightful invention” on the OST, the reference that leaps to mind is George Antheil’s