Into the bald pate of Cassander,

Whose shrieks shatter the air,

Pierrot cranks (hamming it up,

With tender care) – a cranium drill!?

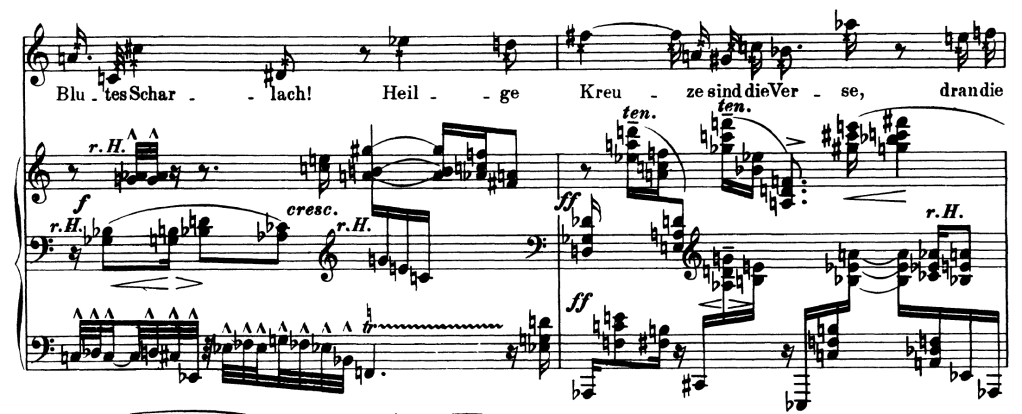

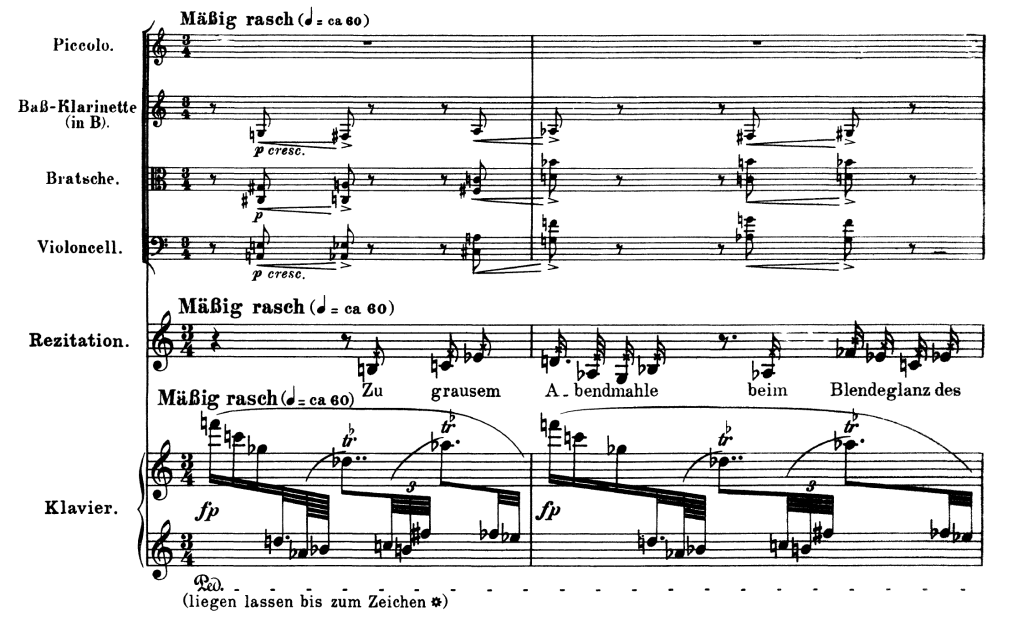

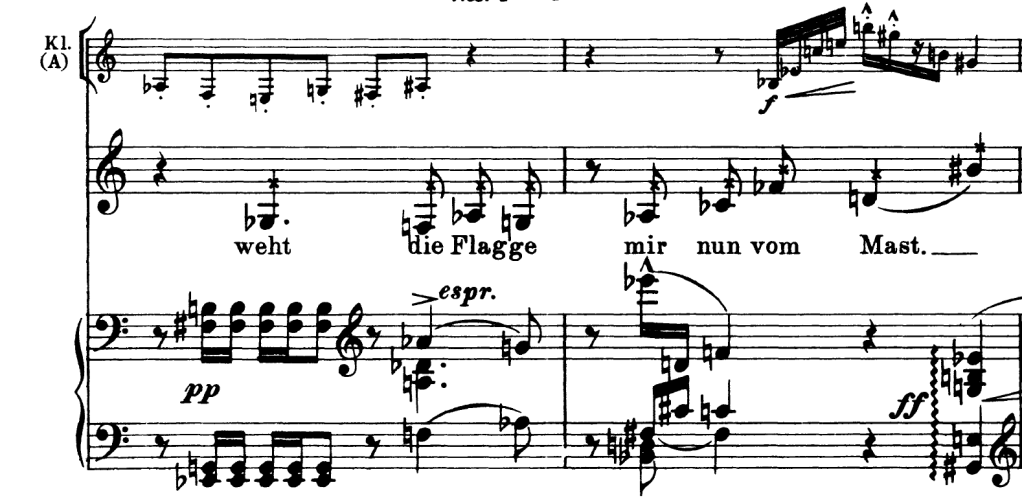

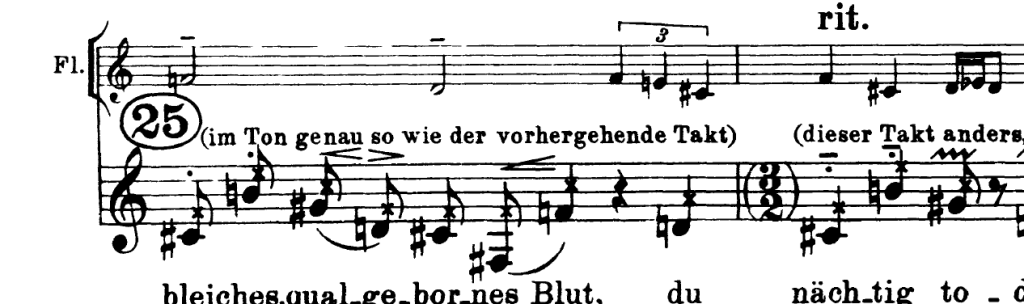

As awful as it is (Gemeinheit: “foul play”; “nasty trick”; “just plain mean!”), it’s all actually quite funny, this one, if you’re in the right sort of mood. Just read the poem – all about Pierrot stuffing fine Turkish tobacco into Cassander’s head while he wails in agony, inserting the pipestem made of Vistula sour cherry wood, and smoking him, “comfortably” – and it might simply seem grotesque, but the music shifts it toward farce, I think. Does it ruin the joke to explain it? And yet look at Schoenberg’s brilliant comic timing after the line about Pierrot’s mock tenderness: a pause, then the punchline – “a cranium drill” (einen Schädelbohrer) – in the vocalist’s most deadpan basement range. The piccolo and clarinet cackle their goofy, razzmatazz laugh track. We are in a performance! Pierrot, fully costumed, has at last come into his own, is doing what he was born to do. He’s cutting up, and the crowd goes wild.

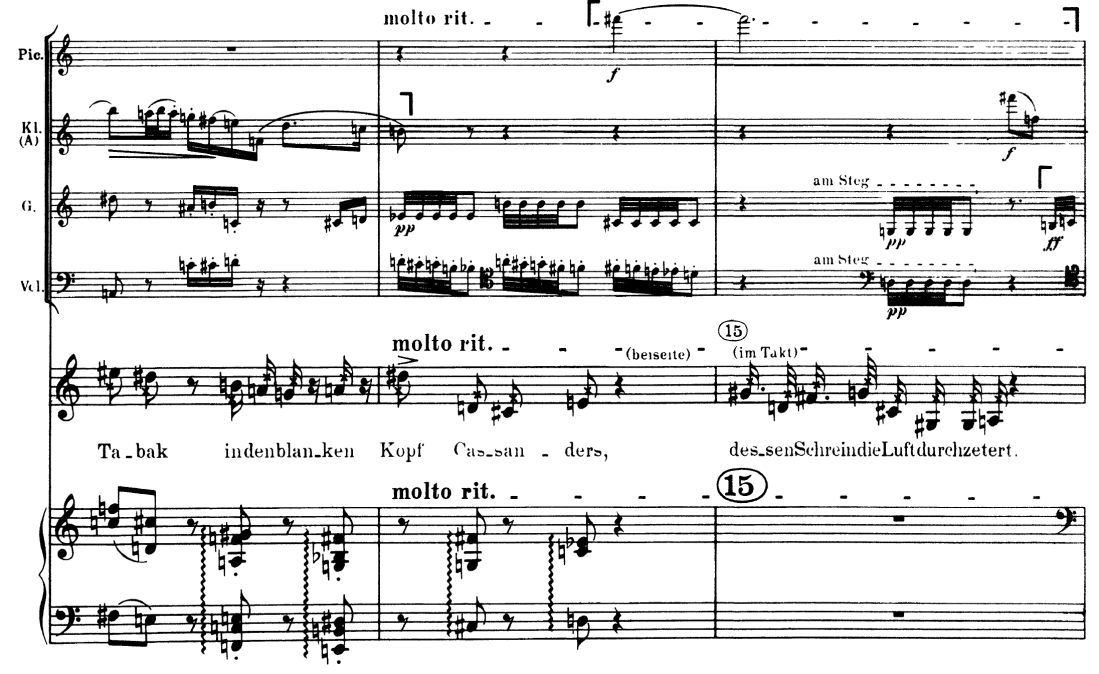

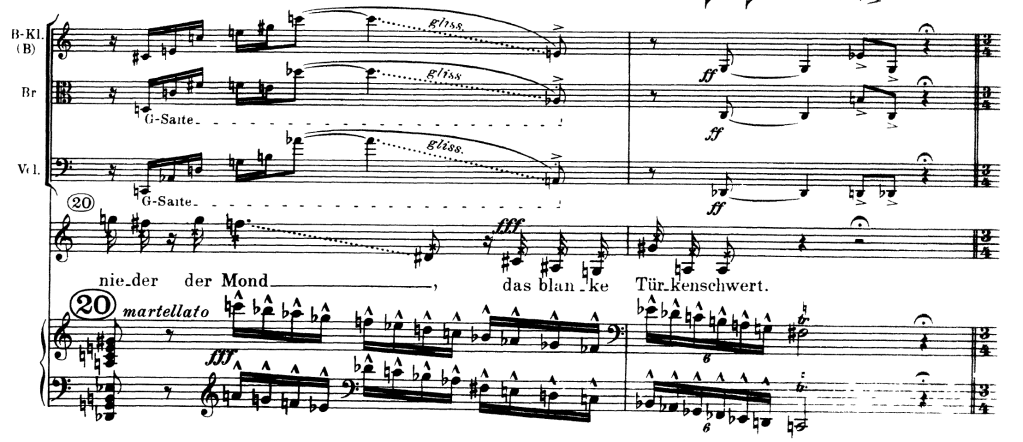

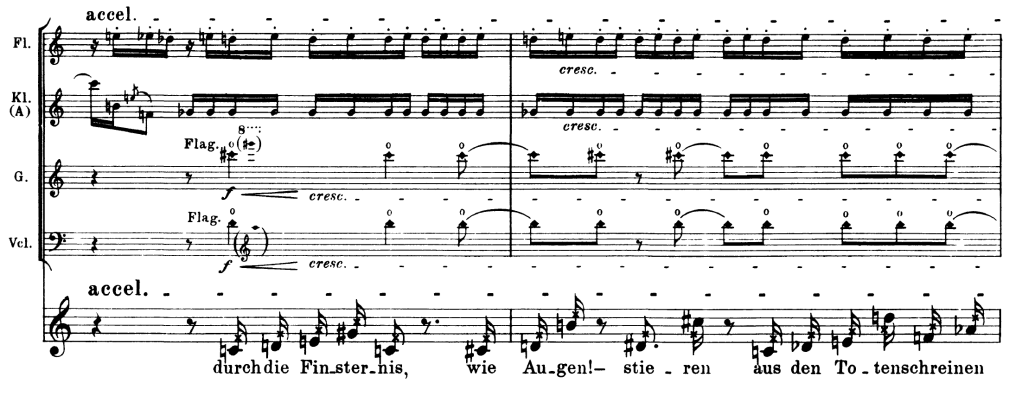

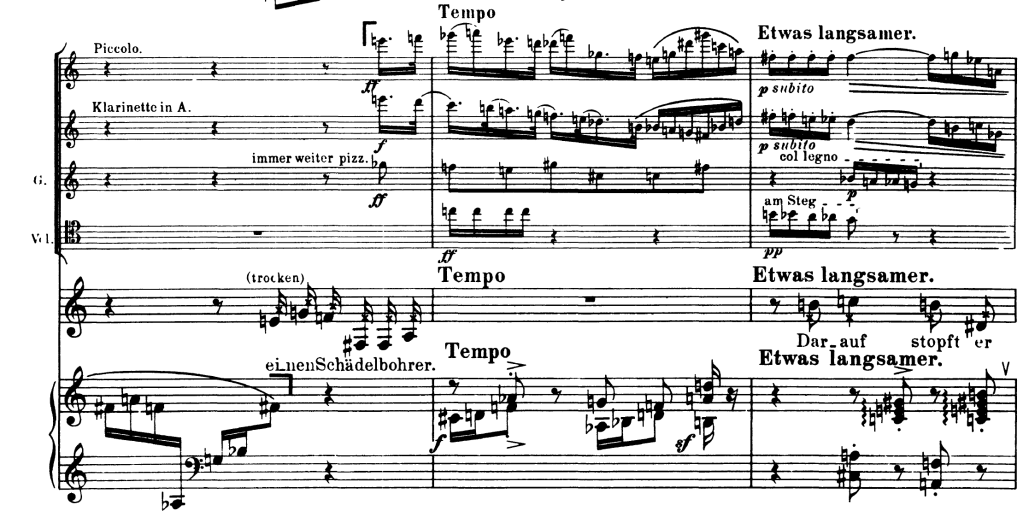

Schoenberg is so economical, his language so packed with purpose, that the piccolo-and-clarinet laugh track isn’t just that. Look at how, at the end of the bar (m. 8), the duo have sextuplets in contrary motion for the turning of the cranium drill, and how immediately in the next bar they’ve traded it for the gruff, four-square repeated sixteenth notes with chromatic motion that opened the movement in the cello. I’m fascinated by the last gesture, I suppose because it’s less clear what it’s doing, but my sense of it is as follows: Pierrot is “rolling up his sleeves and getting it done,” a kind of nonchalance as he matter-of-factly shows the drill to the audience, perhaps, or checks that he has the right drill bit in, etc. Maybe you visualize it differently, but however you do, it’s still three meaning-rich gestures in four beats: one responding to the vocalist’s Schädelbohrer line, one mimicking the drilling motion, and one conveying character and giving us a sense of return in the movement.

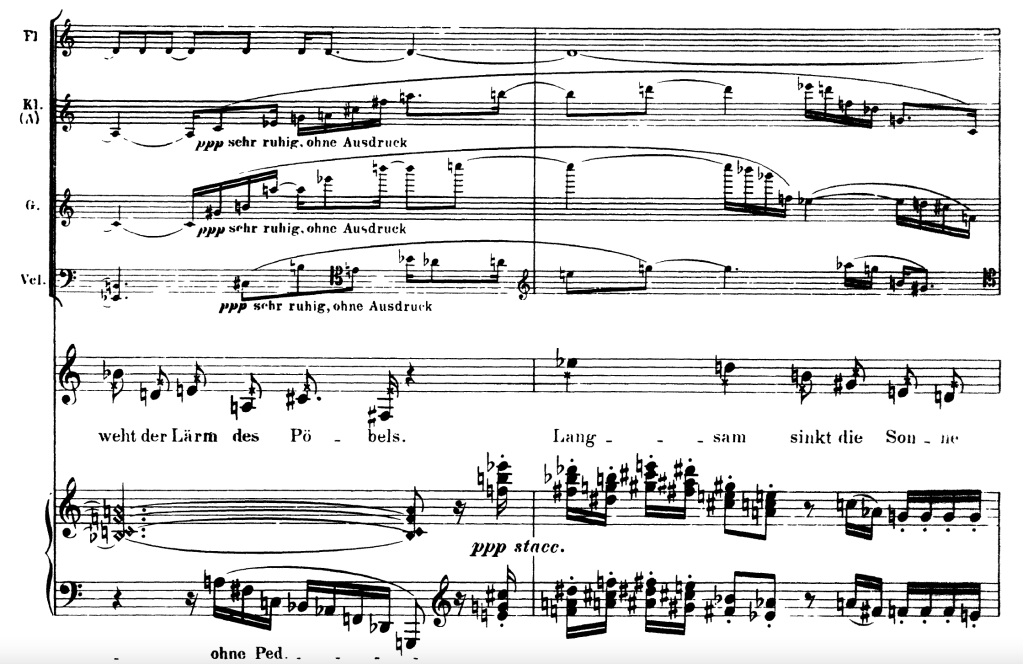

Since Giraud and Hartleben describe Cassander’s squeal in the poem, Schoenberg couldn’t very well leave it out of the music, could he? And there it is in m. 14, that hilarious isolated piccolo F sharp, just before the vocalist tells us what it is (“dessen Schrein” = “whose shriek”). But just as uproarious is the clarinet hee-haw at the end of the next bar, which makes me think of Mendelssohn’s music for Bottom as a donkey in the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The section after this all the way up to the end of the movement is consumed with the gruff repeated-note gesture, now exchanged among the instruments of the ensemble. It’s music of movement or activity underlying Pierrot’s sticking in the pipestem and puffing away. But Schoenberg brings back the laugh track razzmatazz (now in the piccolo and piano) for the final words of the poem: big finish; everybody cheers! And what about that note held over in the cello. . .spotlight on Pierrot? Plunks (piano) in the other instruments as lights out? Again, it’s a performance, from beginning to end.