Pardon the title. I’ve been reading too much John Le Carré, possibly.

Most recently it was The Looking Glass War, but not too long before, it was that most quintessential of double agent novels, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, with its atmosphere of morose dejection and disaffection, of betrayal at every turn by so many sacred cows. [1]

Mutatis mutandis…

Et tu, C major?

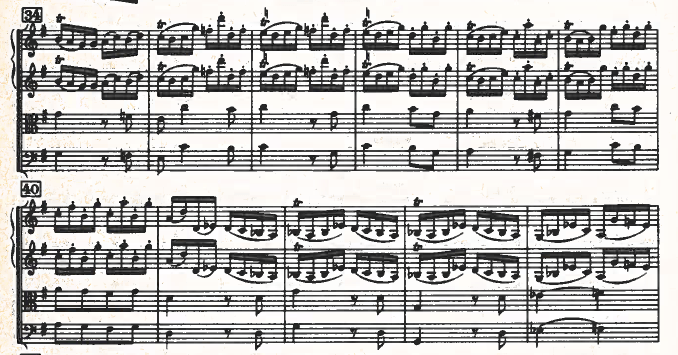

Here we are in Haydn’s Second Symphony in “C Major” (wink), and, in the opening Allegro, the second theme group is in the dominant minor instead of the expected dominant major. [2] But the galant Andante will be better behaved, surely? Not so. The second period similarly falls into the dominant minor, and with this particular theme – a perpetuum mobile with a tic of a trill – that really does seem a surprise. After what sounds to me an almost asphyxiated return to the major, we plunge into the depths for another dose of minor.

You’ll just have to hear it to understand how strange it is for such a theme, in such a brief movement, to lead us time and again into the dark corners of this Arcadia. But then comes the joyous Presto – Haydn really could write a catchy tune, you know? – which couldn’t possibly have room for the minor, could it? Wrong again! After the opening rondo theme, we move to minor and stay there the length of the episode, returning to major for the rondo theme.

Are you following?

In each of the three movements (Italian design again) of Haydn’s Second, there is a significant role for the minor mode, not just as an interesting place to visit in a developmental passage, but as a structural component, a curtained room in C major’s sunlit estate.

Let’s articulate, then, what C major is meant to be. 1) The God key, as in that unforgettable arrival of Light at the dawn of Haydn’s Creation (1797–8). 2) Or the King key. 2+) Or the Queen key, like in Haydn’s second Te Deum (c. 1800), written for Empress Maria Theresa and opening in a blaze of C major. (Yes, fine, there’s a passage in the parallel minor, appropriately pitiful and pious, for the bit about helping us, “thy servants, who thou hast redeemed with thy precious blood,” but that couldn’t very well stay in major, could it?)

How do we hear large minor-mode sections in works governed by the key meant for gods and kings? Possibly the minor mode ennobles – an older way of hearing it, I’d say, and an idea we’re bound to come back to. Or possibly it undermines, throwing shade on the royal sheen. The first possibility is safer, analytically, and of course not everything rides on mode; so many other factors give a minor-mode section its particular character. On the other hand…

There’s something like a tradition of overthrowing King C major. Consider Mozart’s “Dissonance” Quartet, K. 465 (1785), coyly “in C” with that introduction of chromatic excess yielding to an exposition of bunnies-and-butterflies frolic. (OK, they’re very lyrical and charming bunnies and butterflies.) He had a chance, did Mozart, to take a page from Haydn in his second group, but, no, relatively unsullied G major is just fine for his secondary key, thanks. The development’s a slightly different story, but it’s really not until the second movement, which is mostly wistfully beautiful, that Mozart gives us a phrase of properly mournful minor.

Can undercutting C major in the eighteenth century be revolutionary behavior, or, in keeping with the overstory of this blog series, can it be an act of resistance? “God save the King” in “scare quotes”? We are, after all, talking about the century of the American and French revolutions. Just how disruptive do we allow Haydn’s modal usurpations to sound in our ears? Is it playful and harmless ribbing, or the coded rebellion of the Shostakovich of legend? Haydn has never seemed closer to the Sex Pistols. Someone make a meme.

And speaking of secret rebellion… that second movement really is weird. Two-voiced, and, as I mentioned above, a perpetuum mobile for the violins, who inflect their galant line with the occasional trill on the first sixteenth of the measure. I also alluded to the relative extremities of range in this movement. Despite its brevity – about three minutes in most recordings – and the consistency of its materials, the violin part spans two and a half octaves, with passages “seated” in each of three octaves. The effect is just a bit disconcerting and possibly becomes more so the more you listen to it. For Landon, the movement held “a hideous fascination, like the painted grin of a Harlequin in one of those open-air Punch & Judy shows that used to be a feature of the Roman parks in summer.” [3] What a thing to write, H. C.! Little wonder, perhaps, that this comment doesn’t appear in the liner notes (also written by Landon) for the The Complete Symphonies set with Dorati and the Philharmonia Hungarica, even though much of the rest of the commentary on the Second Symphony matches that in the first volume of Landon’s Haydn: Chronicle and Works. [4] I’m sure that difference mostly has to do with form: liner notes have to be more concise than summative tomes. Nevertheless, I can’t help but see in Landon’s rogue comment the very kind of thing that he hears in Haydn’s second movement. It’s a flash of grotesquerie: a jab at convention and a flash of personality, a reminder that in Haydn’s world, as in our own, it’s often an admirable quality to struggle at our bonds.

[1] “I don’t think so, Blackadder – not in the Bible. I can remember a fatted calf, but as I recall that was quite a sensible animal.”

[2] Landon writes, “The second subject of the Allegro is, as usual, in the dominant minor,” but can a “usual” practice really be claimed in a symphony written this early, when its numerical (not necessarily chronological) predecessor (No. 1) moves to the dominant major in the equivalent spot? To look for “usual” practice, it makes more sense to look, say, at early C major quartets: the first movement of Op. 1, No. 6, for example, which, for its secondary key, moves to?….G major, of course! At most, one might speak of moving to the dominant minor for the secondary key as an example of Haydn beginning to explore what will become his tendencies. H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: The Early Years, 1732–1765 (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1980): 287.

[3] Ibid, 287.

[4] The Complete Symphonies of Haydn: Volume Eight, Haydn Symphonies Nos. 1–19, Antal Dorati, dir., Philharmonia Hungarica, notes by H. C. Robbins Landon (New York: Decca Record Co. STS 15310-15, 1973): 14. Note that the “first American edition” of Haydn: The Early Years followed the Dorati set by five years; it’s possible that the comment about Punch & Judy and summertime in Rome emerged in those intervening years, something that only occurred to him the longer he lived with it. I imagine Landon, in his mid-fifties, thinking carefully about what Haydn in his mid-twenties was doing writing something thus tinged with the bizarre.

Reality like exploding pagers and walkie-talkies or one day soon even exploding toothbrushes and razors is leaving espionage fiction in the ashtray of history. Why not forget about fictional agents like Bond and Bourne dashing to save the world from disaster? Why not forget about CIA and MI6 officers reclining on their couches dreaming up espionage scenarios to thrill you? Check out what a real MI6 and CIA secret agent does nowadays. Why not browse through TheBurlingtonFiles website and read about Bill Fairclough’s escapades when he was an active MI6 and CIA agent? The website is rather like an espionage museum without an admission fee … and no adverts. You will soon be immersed in a whole new world which you won’t want to exit.

After that experience you may not know who to trust so best read Beyond Enkription, the first novel in The Burlington Files series. It’s a noir fact based spy thriller that may shock you. What is interesting is that this book is apparently mandatory reading in some countries’ intelligence agencies’ induction programs. Why? Maybe because the book is not only realistic but has been heralded by those who should know as “being up there with My Silent War by Kim Philby and No Other Choice by George Blake”. It is an enthralling read as long as you don’t expect fictional agents like Ian Fleming’s incredible 007 to save the world or John le Carré’s couch potato yet illustrious Smiley to send you to sleep with his delicate diction, sophisticated syntax and placid plots!

See https://theburlingtonfiles.org/news_2023_06.07.php and https://theburlingtonfiles.org/news_2022.10.31.php and https://theburlingtonfiles.org/news_2024.08.31.php.

LikeLike

Not quite on topic, but I like “delicate diction, sophisticated syntax, and placid plots.” Well alliterated!

LikeLike

Glad you like it!

LikeLike