Sometimes an album is like a snapshot. Summer 1967: the summer of Sgt. Pepper’s, when the world of “popular music,” whatever that was, became something else. The snapshot was of a changing world, a record of kinesis between this and that, the high jump captured in mid-air, time miraculously frozen. But Sgt. Pepper’s is an easy example: an album that wanted to be understood as a moment, that knew it would be a moment before it was one, as the gathered dignitaries on its iconic cover so memorably demonstrate. (What else could have convinced them to show up?)

British (Scottish, we should say!) composer Sally Beamish also gives us a snapshot with her album The Imagined Sound of Sun on Stone, which is also the name of the last work on it, essentially a one-movement concerto for saxophone and orchestra. Released after the decade of her meteoric rise (the 1990s) but before her more recent acknowledgment as a major composer of the last quarter century, the album includes works that chart that rise and articulate her compositional journey, a gradual tapping into a deep well of creativity that connects to her identity.

(Nexus entry.)

The Caledonian Road (1997), first work on the album, is named after the road in North London where Beamish’s family went shopping when she was growing up. As she explains in the liner notes, the road really was the road to the north – to that place the Romans called Caledonia, the frightful region beyond the reach of Empire. This was also the place to which Beamish moved in 1990, a move described as “the most important of her career.” So The Caledonian Road, while seeming simply to point to Scotland, is also autobiographical and has to do with Beamish’s personal road to Scotland. The sound of the north seems to be present in at least two ways in the work: through a pastoral style conjured by lyrical wind lines over string drones and through specific reference to a complex of musical sources – “ancient bells,” horn calls, and fragments from the St. Andrews Music Book (that is, W1. . .that is, Wolfenbüttel 1, that is, Cod. Helmst. 628, which, as every musicologist of a certain age knows, is one of the major repositories of the Magnus liber organi). Beamish had brought these sources together before in St. Andrew’s Bones (1997), a work for horn, violin, and piano, which was also inspired by the ruins of St. Andrew’s Cathedral in the county of Fife in Scotland, ruins the composer had heard described as “like the rib-cage of some long-dead god.” And so the work is autobiographical in layers, touching on the composer’s childhood and on another work of hers, with its related but distinct set of referents. One of the most unusual qualities of the work to me is its essentially non-dramatic nature. Despite the fact that the largest number of “bell bursts” is saved for the end, the end is really no louder or more impressive than other moments throughout the work. The notes describe the work as being in “variation form,” with variations marked off by those “bell bursts,” combinations of chime sounds and orchestral renderings of bell resonance. Some variations are more active, some more lyrical, and the whole is loosely arranged in a kind of arc shape, with the most active, densely contrapuntal variations inhabiting the central section and the variations with sparser textures bookending the work.

What does such a form suggest if the title points to journey, to a road, and if the notes argue for a sort of narrative dimension where one eventually arrives in a physical and spiritual Caledonia? In thinking about this, it has seemed to me almost as if Beamish structures the work so that the road to the future leads to the past and that the activity of the central section, its agitation, is the movement – a great exertion – that leads back to the beginning. The elliptical journey suggests the preordained, moving forward only to find that the destination was within you, was you yourself in some version you sensed but did not fully comprehend. This is less the unfolding of a drama and more the dawning of enlightenment, the recontextualization of ever-present material.

The idea of moving into the future to get to the past is also present in the second work on the album, The Day Dawn. Without having read the notes, my first thought was that the saturated, slow-moving string sonorities at the beginning were reminiscent of Górecki’s Symphony No. 3, called the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs because of the texts, concerned with mothers and children, and more particularly with the loss of children. And then I read the notes. Beamish wrote the piece, as it turns out, as an act of public mourning for a friend of hers whose young daughter had died. Perhaps, therefore, Beamish was deliberately referencing Górecki, or perhaps she couldn’t escape him. But the idea running through the piece, of a parent, a mother, trapped in mourning, greeted by sunshine on the day of the funeral after a week of rain, also suggests the world of Kindertotenlieder, and more specifically of “Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgehn”: “Now the sun will rise brightly, as if nothing bad had happened in the night.” But where Rückert and Mahler are mired in irony, beset by self-doubt, and Górecki makes grief so beautiful that you never want to leave it, Beamish shows us a way out.

That way is an old Shetland fiddle tune named “The Day Dawn,” which was played to celebrate the Winter Solstice, “to mark the dawn of lengthening days,” according to the notes. The tune is heard at its clearest at the very end of the work, a sort of Ivesian solution to form, as if it could only be pieced together a bit at a time over the course of the work. When it is heard in this clearest version, however, it is without the vim and vigor of dance: a vessel that needs to be filled, the shape of life that needs to be stepped into. And here I’m reminded of another line in Rückert’s “Nun will die Sonn’”: “Du mußt nicht die Nacht in dir verschränken / Mußt sie ins ew’ge Licht versenken!” – “You must not become the darkness yourself but must commune with eternal light.” (That’s my attempt, but I’ve often seen it in English as “you must not enfold the night within you but must sink into eternal light.”) How do you enter into the light that exists beyond mourning? Beamish uses that old Shetland fiddle tune to suggest a potent cure: music, dance, activity, the land, home, the rootedness of those things, their ability to subsume individual grief in a larger story, all of which means that life does go on after loss. It’s a kind of ancient wisdom, the wisdom that has the mother dance all night at a wawa verlorio to mourn her child. To live into the future, Beamish has us travel deeper into the past.

Time breaks down in music, becomes a kind of riddle. Brevity stands for length, forward stands for backward. We are time travelers, set adrift in a timeless soundscape.

Beamish, as I’ve said, lets the last work on the album, The Imagined Sound of Sun on Stone, give its name to the whole. And the way that work plays with sound and time will now seem iconic for the album and composer. The material, according to the notes, comes from various places and times: an old Swedish herding call, “psalms and chants coming from different traditions,” “blues,” though I think this is an oversimplified way to describe a much more sophisticated jazz-inspired idiom, which sometimes steams and screams like Coltrane and sometimes simmers and sneaks like a gumshoe in postwar film noir. Beamish is kind enough to describe the form of the work in her notes, and I would gloss her description as “accumulation, arrival, dispersion.” The arrival happens a little over halfway through the twenty-minute work and is a true climax on an album of few overt climaxes: an explosive, gripping burst of C major, which the composer describes as “the moment at the solstice when light enters the prehistoric tomb.” That arrival shatters conventional time. It serves as a sort of portal into a place where jazz and ancient chant exist in swirling simultaneity – a universal “hymn” in the Ivesian sense of a thousand different voices singing their thousand different songs at once. Gradually the elements released by this C-major arrival, which seems to me a cousin of the Sanctus from Britten’s War Requiem, scatter and fly away, but a cycle has been established: seasons flow, and the solstice will come again, letting past and present dance together until the tomb goes dark.

The other piece on the album, I’m not afraid (1989), is also fascinating. An early work, one that Beamish apparently considers crucial in her compositional development, it is a sort of response to six poems by Ukrainian poet Irina Ratushinskaya (1954-2017), which are read (by the composer!) as the chamber ensemble provides an accompaniment that is part filmic underscore, part expressionistic Pierrot-like mimesis. The clown logic of the piece may connect to the poet’s history. A Christian dissenter in the Soviet Union, imprisoned for almost four years, who wrote poetry throughout her imprisonment, some of which was smuggled out on scraps of paper: this is the sort of grim grotesquerie that would seem to require the surreal distancing techniques of Pierrot to achieve anything other than the bleakest tragedy. I would love to write about Stravinsky in the work, about the special role for oboe, and yes, about clown logic, but for this entry maybe it’s just as important to note that in 1989 Beamish was already “singing” the song of the dispossessed, of the woman imprisoned, yearning to seize freedom. On this album she has shared that sound of yearning, in her own human voice, before showing us the ancient destination that lay on the path ahead.

(Nexus exit.)

You see, sometimes an album is like a snapshot. . .

Blake (b. 1949) is a dyed-in-the-wool Kiwi: born in Christchurch, educated at Canterbury University, and now Chief Executive of the

Blake (b. 1949) is a dyed-in-the-wool Kiwi: born in Christchurch, educated at Canterbury University, and now Chief Executive of the  The poems are printed in full in the liner notes, and emblazoned across the album art as an epigraph is this quote from the second of them, from which Blake says the music takes its “mood of restlessness”: “Always, in these islands, meeting and parting/Shake us, making tremulous the salt-rimmed air.”

The poems are printed in full in the liner notes, and emblazoned across the album art as an epigraph is this quote from the second of them, from which Blake says the music takes its “mood of restlessness”: “Always, in these islands, meeting and parting/Shake us, making tremulous the salt-rimmed air.” The recent thought-provoking volume The Sea in the British Musical Imagination, edited by

The recent thought-provoking volume The Sea in the British Musical Imagination, edited by  When a descending trumpet figure cuts through the hymn texture, at first it feels like a response to Charles Ives’s Unanswered Question, in which the strings’ slow-moving hymn is cut through by the questioning trumpet. But there’s more to Blake’s trumpet than a dissonant question; as other instruments take up the figure, it reveals itself not as a human but as avian. To wit, the call of the

When a descending trumpet figure cuts through the hymn texture, at first it feels like a response to Charles Ives’s Unanswered Question, in which the strings’ slow-moving hymn is cut through by the questioning trumpet. But there’s more to Blake’s trumpet than a dissonant question; as other instruments take up the figure, it reveals itself not as a human but as avian. To wit, the call of the  The second, while fulfilling its memorial function admirably, also references a special kind of twentieth-century orchestral writing that I think owes a considerable debt to nature documentaries. The final work on the album is also the most recent: The Furnace of Pihanga (1999), inspired by a Maori story about the contest of mountain gods “for the love of the beautiful Pihanga.” There’s a sensitive timbral imagination on display here, and it’s a pleasure to hear Blake tell the story described in his liner notes through the orchestral medium.

The second, while fulfilling its memorial function admirably, also references a special kind of twentieth-century orchestral writing that I think owes a considerable debt to nature documentaries. The final work on the album is also the most recent: The Furnace of Pihanga (1999), inspired by a Maori story about the contest of mountain gods “for the love of the beautiful Pihanga.” There’s a sensitive timbral imagination on display here, and it’s a pleasure to hear Blake tell the story described in his liner notes through the orchestral medium. I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven.

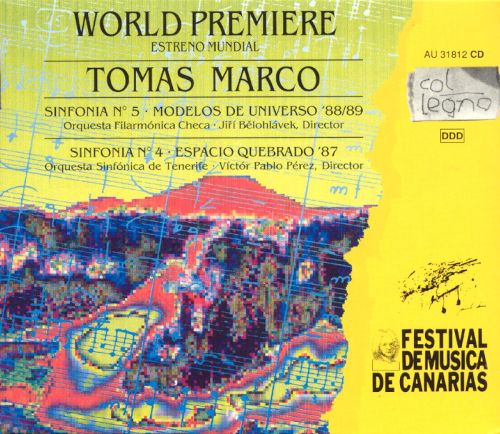

I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven. Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between

Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between  In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. But perhaps it’s better to read the composer’s explanation of the work’s background: “Growing up in Cuba was a kaleidoscopic experience with sound. . .You have all of these revelers in the back of my home, preparing themselves for the Carnival. Even when I was actually trying to play Chopin or Tchaikovsky or, you know, I mean, Czerny, they would parade in front of the house, I would stop playing the piano, go, see the revels pass by, and when they pass by, we all dance, you know. And then, when they were gone, everybody went back to their chores. I went back to the piano; I continue practicing. . .Of course, upon my return [to Cuba, years later], I realize that the revelers were not there anymore, and these are just my memories.” [1]

But perhaps it’s better to read the composer’s explanation of the work’s background: “Growing up in Cuba was a kaleidoscopic experience with sound. . .You have all of these revelers in the back of my home, preparing themselves for the Carnival. Even when I was actually trying to play Chopin or Tchaikovsky or, you know, I mean, Czerny, they would parade in front of the house, I would stop playing the piano, go, see the revels pass by, and when they pass by, we all dance, you know. And then, when they were gone, everybody went back to their chores. I went back to the piano; I continue practicing. . .Of course, upon my return [to Cuba, years later], I realize that the revelers were not there anymore, and these are just my memories.” [1] The connection is suggested in part because of the episodic nature of Parajota Delaté: a gait is established, then arrested and joined to the next by an interlude, as often in Pierrot. I hear fleeting references to “Enthauptung,” “Serenade,” “O Alter Duft.” Is León suggesting some alternate reading of the Pierrot narrative or exploring the ensemble in a way that playfully interacts with one of the touchstone works of the twentieth century? According to Ellen K. Grolman’s Grove article on Joan Tower, the composer “sometimes offer[s] musical salutes in titles of her works” (e.g.,

The connection is suggested in part because of the episodic nature of Parajota Delaté: a gait is established, then arrested and joined to the next by an interlude, as often in Pierrot. I hear fleeting references to “Enthauptung,” “Serenade,” “O Alter Duft.” Is León suggesting some alternate reading of the Pierrot narrative or exploring the ensemble in a way that playfully interacts with one of the touchstone works of the twentieth century? According to Ellen K. Grolman’s Grove article on Joan Tower, the composer “sometimes offer[s] musical salutes in titles of her works” (e.g.,  It’s a work of about twenty minutes for six amplified voices and percussion, on a text created by the collaborators in a mixture of Spanish, Yoruban, a Cuban dialect, “nonsense syllables,” and a little English. Sometimes it reminds me of Steve Reich’s Tehillim (1981), another work situated at the fruitful intersection of art music and a distinctive linguistic and spiritual heritage. In Batéy’s third movement, “Rezos” (“Prayers”), composed entirely by León, I hear a debt to Luciano Berio’s choral writing, particularly as found in “O King,” the second movement from Sinfonia (1969). The final word in “Rezos” is the English word “DREAM!” which references the famous speech by Martin Luther King. Why? A batéy is a slave village at a sugar plantation; the text of the piece fittingly centers on labor and oppression, on the one hand (and also weather, which perhaps signifies powerful forces beyond our control), and, on the other, the freedom achieved through ritual, community, and music. Perhaps this collection of ideas suggests parallels with the civil rights movement in the U. S., which in turn anticipates León’s current operatic project, Little Rock Nine.

It’s a work of about twenty minutes for six amplified voices and percussion, on a text created by the collaborators in a mixture of Spanish, Yoruban, a Cuban dialect, “nonsense syllables,” and a little English. Sometimes it reminds me of Steve Reich’s Tehillim (1981), another work situated at the fruitful intersection of art music and a distinctive linguistic and spiritual heritage. In Batéy’s third movement, “Rezos” (“Prayers”), composed entirely by León, I hear a debt to Luciano Berio’s choral writing, particularly as found in “O King,” the second movement from Sinfonia (1969). The final word in “Rezos” is the English word “DREAM!” which references the famous speech by Martin Luther King. Why? A batéy is a slave village at a sugar plantation; the text of the piece fittingly centers on labor and oppression, on the one hand (and also weather, which perhaps signifies powerful forces beyond our control), and, on the other, the freedom achieved through ritual, community, and music. Perhaps this collection of ideas suggests parallels with the civil rights movement in the U. S., which in turn anticipates León’s current operatic project, Little Rock Nine.