First impressions matter.

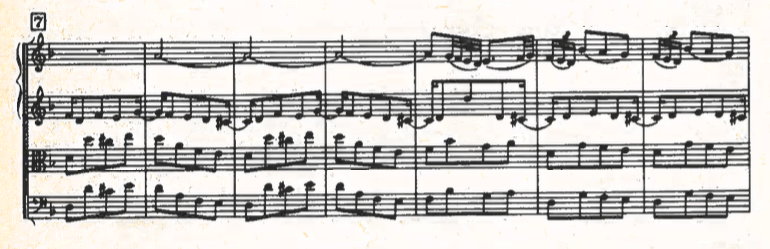

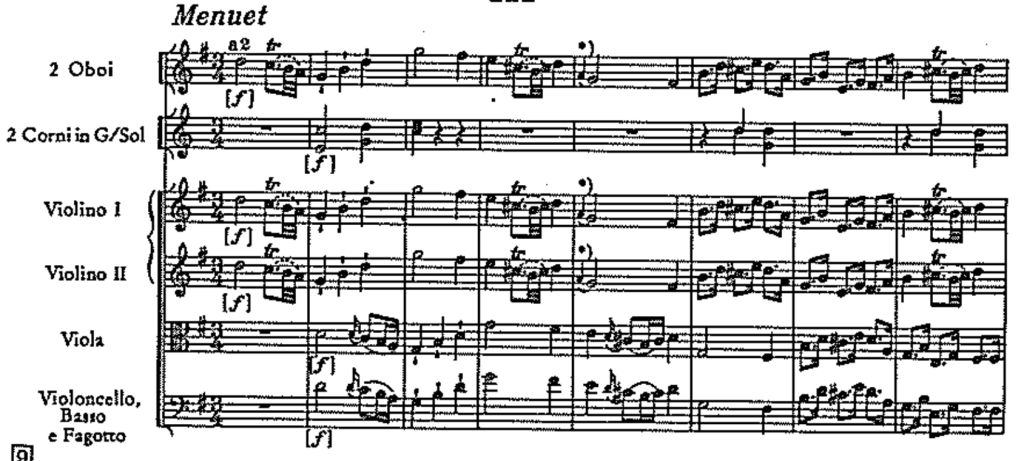

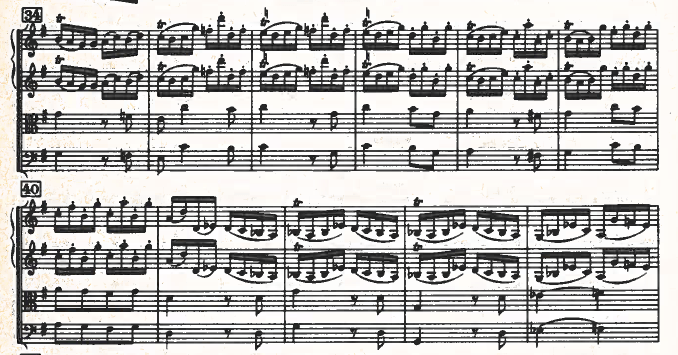

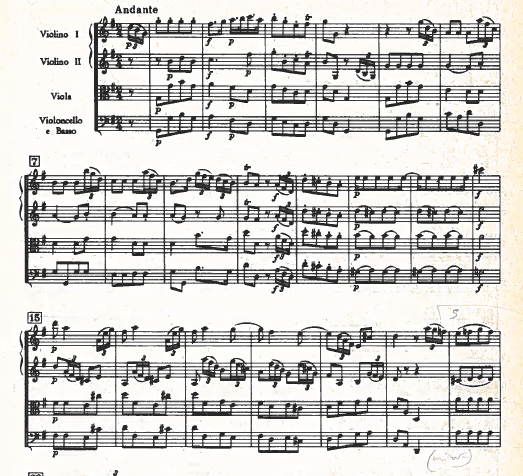

Seriously. Who would ask this of a pair of hornists in 1760?

But you should also really consider the (unhinged?) Trio from the third movement. Observe, please, the total absence of any safety net, the radical exposure of the hornists. Were they quaking in their liveries, one wonders? Forget the mannered surety of “hunting horn figures” – these fellas are stalking the jabberwock with laser cannons. Or maybe it’s more like Die schöne Müllerin meets Hair.

This can’t be normal, can it? My initial impression, at least, was that it can’t be. In other words, not the kind of horn writing that seemed tricky in a genteel, doily-dappled past but would gradually become old hat to your average monster hornist. This horn writing sounds like it would remain treacherous. As evidence I note that YouTube offers no live performance, as far as I can tell. And had there been a live performance, just what facial expression might that pair of hornists have worn the bar before their entrance… Grim resolve? Silent appeal to the divine? Rabid-dog excitement? [1]

But then I turned to someone who, you know, actually plays and researches natural horn, fellow San Antonian Dr. Drew Stephen, who explained that the demands Haydn puts on his hornists in the Fifth Symphony are “a little unusual, especially for an early symphony,” but not exceptional. [2] Haydn’s writing in the Fifth simply expects that the hornists would have been comfortable playing in the clarino register, that’s all. Not worlds apart, I suppose, from the bracing effect of clarino trumpet in Brandenburg No. 2. To us lesser mortals it might seem a miracle, but it was once someone’s day job.

My analytical process is always to listen with the score first and to develop my thoughts a bit before turning to other writers, etc. – put it down to anxiety of influence, which is to say that I suspect my own unusual perspective will emerge with greater clarity in the absence of other people’s ideas – and that’s what I did this time. But then, after the eye-popping, spine-tingliness of this horn experience, I turned to my trusty copy of Chronicle and Works, and read this from Landon: “Hardly have the strings begun [in the first movement]…than the solo horns enter with a passage of greatest difficulty [italics added].” And this about the Trio: “This [folk-like] atmosphere is…enhanced by the solo horns (again reaching sounding a’’) and solo oboes.” [3] Yes, Landon half-dresses it up in regalia, but you know what he’s saying, right? Psycho horns. But, pace Landon and my own first impression – sometimes it’s best to trust the experts!

For what it’s worth, the second and fourth movements don’t make such demands. At first, I wondered if Haydn felt he could only get away with asking such things of his hornists if he gave them a smoke break every other movement. That’s what the composer in me might do on a friendly sort of day. And there is a bit of an interrogation atmosphere in this symphony, with alternating bad cop and good cop movements. But here, too, the good Dr. Stephen has assured me that no recovery time would have been needed. “Once you get in that [clarino] groove, it is not particularly tiring.” So maybe Haydn was even being overly cautious by “underwriting” in the second and fourth movements, the opposite of my initial impression. Still, I console myself by observing, in Drew Stephen’s kindly compiled list of clarino horn ranges in early Haydn symphonies, that Papa H. only ever exceeded the (sounding) highest note of the Fifth Symphony once, and then by a half step. So H. I:5 is high, OK? It is! It’s just maybe clarino high instead of psycho high.

Of course I’m being a tad bit silly. All the above might give you the impression that the hornists were bad and that Haydn was punishing them by writing such high parts, but the opposite is more likely. I would guess that Haydn met a couple of hornists – at Count Morzin’s, or perhaps a couple of guest artists? – who were so phenomenally good, so completely rock-solid reliable, that he wrote the symphony with them in mind so they could show off. And, when they performed it? Doubtless the Countess Wilhelmine would have fluttered her fan most fervently at such ferocious horn shredding.

I mentioned that the second and fourth movements don’t have the same kind of “extreme” clarino horn writing, and this means that Haydn’s Fifth is a four-movement symphony. This does not mean, however, that the four movements follow the (yet-to-calcify) classic Haydn design. It’s something quite different, and this adds to the atmosphere of strangeness in a few ways.

Qu’est-ce que c’est, you ask?

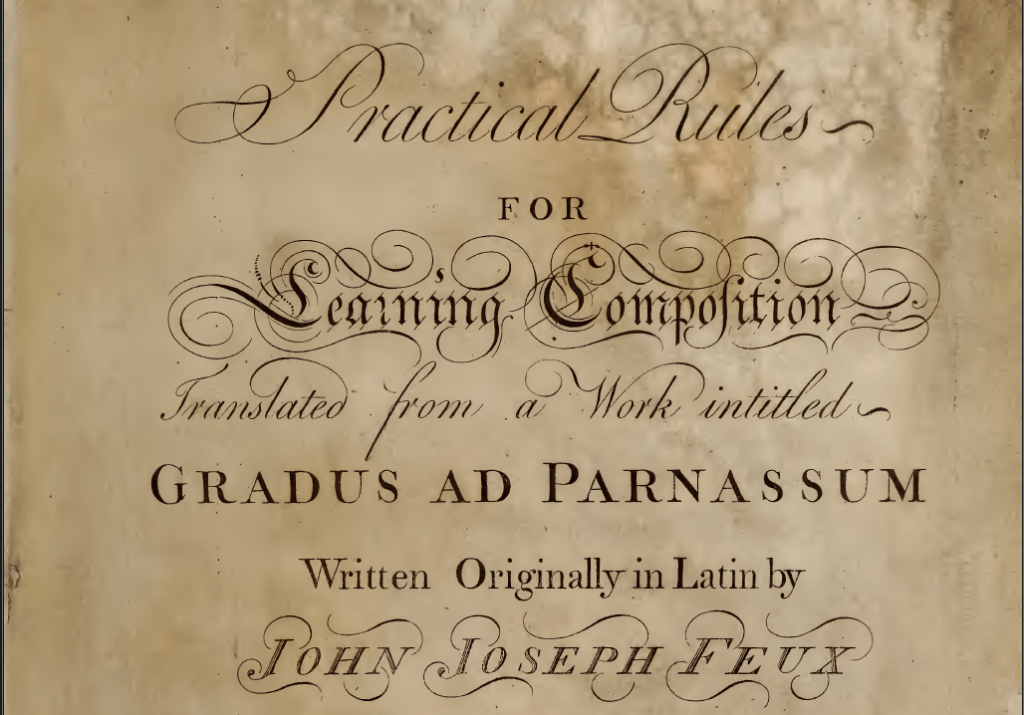

The well-trained musicologist in me did, I admit, recognize in Haydn’s Fifth the outlines of a sonata da chiesa, that by-then old-fashioned four-movement genre with a slow-fast-slow-fast (usually?) design. Oh, you know, the sort of thing Corelli wrote. I wasn’t surprised, therefore, on cracking open my Chronicle and Works to see Landon mention the sonata da chiesa in his comments: “Here is another work in the sonata da chiesa form, opening with an entire Adagio…” [4]

That’s fine up to a point, but the curious thing is that the opening Adagio of H. I:5 is nothing like the kind of slow movement that Corelli would have written. We can easily see the outlines of sonata form in it, albeit with underdeveloped secondary material. Further, instead of giving us a slow third movement à la sonata da chiesa, he gives us a minuet-trio, as we expect in what will become Haydn’s normative symphonic plan. In other words, H. I:5 is a work sui generis and in generic transition, tugging between the Italianate three-movement symphony, the older sonata da chiesa, and the Haydn four-movement design of the future.

Landon drops us another nugget of knowledge in his commentary, and this one gave me an opportunity to learn something new. “Here, in No. 5, we have an interesting example of the divertimento-cassatio technique being applied to such a solemn, slow movement: hardly have the strings begun by themselves (leading us to believe that this is a typical wind-less slow movement) than the solo horns enter…” [5] And you probably remember the rest, or, if you don’t, you can browse the top of this entry. Ye olde “divertimento-cassatio technique,” eh? I had to do some homework for this one – SHOCK! – and strolled for a bit in a budding Grove (Music Online) to get a better handle on “the cassation.”

And?

I’m afraid it’s complicated, as so many generic designations are in the 17th and 18th centuries. What to share? Well, after some wrangling about etymology, the Grove entry writers land on the German Grassaten or Gassaten as the origin of the term cassation, connected to a saying current among mid-18th-century musicians that meant “to perform in the streets” (“gassatim gehen”). [6] So it seems that a cassation has to do with playing outside, which suggests (loud) wind instruments, which in turn explains Landon’s comment about the first movement of the Fifth Symphony, where we’re tricked by the instrumentation and tempo of the opening to expect inside music (strings sawing sweetly) only to be jolted awake by outside music: horns, just about as high as they could go.

Don’t miss this, though! After all is said and done, this opening movement – whatever alchemical amalgam of sonata form and sonata da chiesa and cassation – is an Adagio, and that makes Haydn’s Fifth the first of the numbered symphonies where the slow movement is the first thing we hear and also the first in which a slow movement has wind instruments at all. The wildness of the horn writing, if that’s what it is, is therefore of a piece with the wildness of Haydn’s formal invention.

And that makes Haydn’s Fifth fa-fa-fa-fa, fa-fa-fa-fa far better, I’d say, than the AI-generated mashup of David Byrne+Haydn playing the horn (?) that you will now possibly not be able to unsee.

[1] When do I get paid?

[2] Many thanks to Dr. J. Drew Stephen, Associate Professor of Music History at the University of Texas at San Antonio for an enlightening email exchange about clarino writing, especially in early Haydn! You can hear his introduction to natural horn on his UTSA bio page: https://colfa.utsa.edu/faculty/profiles/stephen-john.html

[3] H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works, The Early Years, 1732–1765 (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1980): 292.

[4] Idem.

[5] Idem.

[6] Hubert Unverricht, rev. Cliff Eisen, “Cassation,” in Grove Music Online, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic.

The second track, “Every Little Kiss,” opens with Hornsby’s piano solo—hardly a surprise, as that was sort of how he carved out his unconventional place in the popiverse of the Reagan years. Through repeated background listening I memorized “every little” nuance of that opening solo.

The second track, “Every Little Kiss,” opens with Hornsby’s piano solo—hardly a surprise, as that was sort of how he carved out his unconventional place in the popiverse of the Reagan years. Through repeated background listening I memorized “every little” nuance of that opening solo.

The atmosphere of quotation begetting quotation that Ives inspires seems echoed, therefore, in the link between the NET film and the LPO recording. This quality is brought out in Serebrier’s extensive program notes, which often reference the 1965 première. In the spirit of Ives, I can’t resist a quotation: “I shall never forget that winter morning at Carnegie Hall, when Stokowski had scheduled the first rehearsal of the Ives Fourth. He stared at the music for a long time, then at the orchestra. I had never seen the score, and my heart stopped when he turned to me and said, ‘Maestro, please come and conduct this last movement. I want to hear it.’ After it was all over, my arms and legs still shaking, I complained that I was sightreading. Stokowski’s reply was, ‘So was the orchestra!’” If they were sightreading on that first day, one of the remarkable things about the première was it was especially well prepared: Stokowski asked for (and got) a number of extra rehearsals, underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See the NET documentary at 7:55 for Stokowski’s explanation, delightfully redolent of the absent-minded professor.) But Serebrier’s recording brought with it almost an additional decade of opportunity to live with the work’s challenges and possibilities, and so it inevitably sounds more refined.

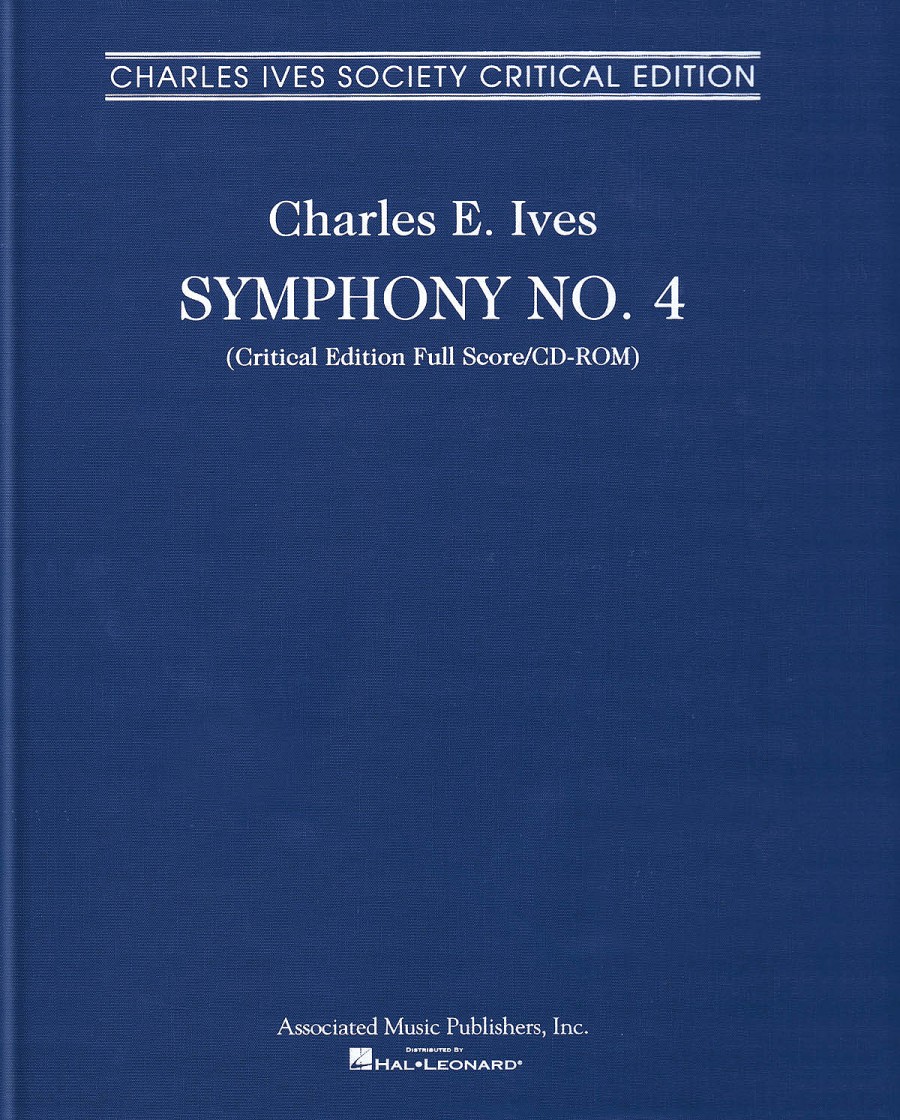

The atmosphere of quotation begetting quotation that Ives inspires seems echoed, therefore, in the link between the NET film and the LPO recording. This quality is brought out in Serebrier’s extensive program notes, which often reference the 1965 première. In the spirit of Ives, I can’t resist a quotation: “I shall never forget that winter morning at Carnegie Hall, when Stokowski had scheduled the first rehearsal of the Ives Fourth. He stared at the music for a long time, then at the orchestra. I had never seen the score, and my heart stopped when he turned to me and said, ‘Maestro, please come and conduct this last movement. I want to hear it.’ After it was all over, my arms and legs still shaking, I complained that I was sightreading. Stokowski’s reply was, ‘So was the orchestra!’” If they were sightreading on that first day, one of the remarkable things about the première was it was especially well prepared: Stokowski asked for (and got) a number of extra rehearsals, underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See the NET documentary at 7:55 for Stokowski’s explanation, delightfully redolent of the absent-minded professor.) But Serebrier’s recording brought with it almost an additional decade of opportunity to live with the work’s challenges and possibilities, and so it inevitably sounds more refined. Still, it is a revelation to listen to Serebrier’s recording while following along with the 2011 Charles Ives Society Critical Edition of the score, with each movement edited by a different scholar from the variety of sometimes conflicting sources. (This extraordinary publication includes a CD-ROM with scans of all of Ives’s manuscript material for the work.) Looking at Wayne D. Shirley’s edition of the fourth movement, for example, shows how much either was excised from or never incorporated into the edition prepared by the staff of the Fleischer Music Collection, used for the 1965 première and the 1974 recording; following the course of almost any single part reveals that much more is possible than got realized under Stokowski or Serebrier. And, well, who can blame them? Ives asks for an entirely different ensemble for each of his four movements, pushing past Richard Strauss into a kind of proto-Gruppen orchestral environment, particularly in the finale. All this in a work of the 1910s and ‘20s. Not that Ives would have recognized the finale in the 2011 Critical Edition as his, per se. As William Brooks brilliantly proposes in the preface to the edition, in the face of the impossibility of creating a single definitive edition of the finale from a multiplicity of sources, “The workable anarchy of Ives’s music is better manifested in his manuscripts than in publications; and it is the manuscripts which you [Who, me?!?!]—through whom Ives’s music sounds—can and should enter. There can be no Ives urtext, no approved edition. In the re-formed world universal access to the manuscripts will bring into being an ever-expanding sphere of visions, performances—‘editions,’ if you will—all shaped for particular times, places, circumstances. I look forward to your contributions.” This quote resonated powerfully with me as I sat there in the stunned aftermath of the last movement, thinking about the beauty of what I heard and the promise of what I didn’t hear but could almost imagine. (More of it is present in other more recent recordings, incidentally.) Could there ever be enough instruments, enough parts to satisfy Ives’s all-encompassing vision? Could there ever be enough refracted and refracting quotations to answer the call? Brooks says no, but he looks forward to a Borges-like infinite gallery of responses. How wonderful to imagine that in writing about it we come to constitute a version of the work.

Still, it is a revelation to listen to Serebrier’s recording while following along with the 2011 Charles Ives Society Critical Edition of the score, with each movement edited by a different scholar from the variety of sometimes conflicting sources. (This extraordinary publication includes a CD-ROM with scans of all of Ives’s manuscript material for the work.) Looking at Wayne D. Shirley’s edition of the fourth movement, for example, shows how much either was excised from or never incorporated into the edition prepared by the staff of the Fleischer Music Collection, used for the 1965 première and the 1974 recording; following the course of almost any single part reveals that much more is possible than got realized under Stokowski or Serebrier. And, well, who can blame them? Ives asks for an entirely different ensemble for each of his four movements, pushing past Richard Strauss into a kind of proto-Gruppen orchestral environment, particularly in the finale. All this in a work of the 1910s and ‘20s. Not that Ives would have recognized the finale in the 2011 Critical Edition as his, per se. As William Brooks brilliantly proposes in the preface to the edition, in the face of the impossibility of creating a single definitive edition of the finale from a multiplicity of sources, “The workable anarchy of Ives’s music is better manifested in his manuscripts than in publications; and it is the manuscripts which you [Who, me?!?!]—through whom Ives’s music sounds—can and should enter. There can be no Ives urtext, no approved edition. In the re-formed world universal access to the manuscripts will bring into being an ever-expanding sphere of visions, performances—‘editions,’ if you will—all shaped for particular times, places, circumstances. I look forward to your contributions.” This quote resonated powerfully with me as I sat there in the stunned aftermath of the last movement, thinking about the beauty of what I heard and the promise of what I didn’t hear but could almost imagine. (More of it is present in other more recent recordings, incidentally.) Could there ever be enough instruments, enough parts to satisfy Ives’s all-encompassing vision? Could there ever be enough refracted and refracting quotations to answer the call? Brooks says no, but he looks forward to a Borges-like infinite gallery of responses. How wonderful to imagine that in writing about it we come to constitute a version of the work. The recording I was listening to, incidentally, was of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales under Mark Wigglesworth, which accompanied the August 1994 issue of BBC Music. In some ways it makes a great deal of sense to listen to this live performance, as the 1964 concert that brought the fully realized Tenth to the world was part of that season’s Proms.

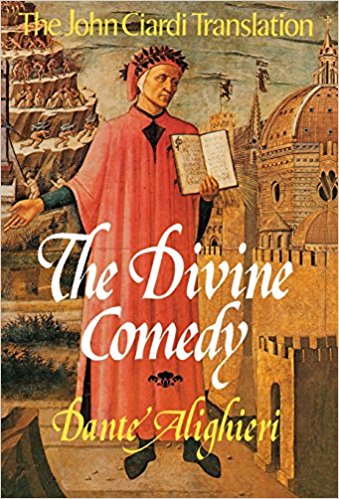

The recording I was listening to, incidentally, was of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales under Mark Wigglesworth, which accompanied the August 1994 issue of BBC Music. In some ways it makes a great deal of sense to listen to this live performance, as the 1964 concert that brought the fully realized Tenth to the world was part of that season’s Proms. He’s the one, after all, who called his middle movement “Purgatorio,” suggesting the epic scope of Dante’s Divine Comedy and practically begging a listener to look for an Inferno and a Paradisio. Or is it really the middle three movements that function collectively as a kinetic purgatory—a waiting place, an interruption—foil to the first movement’s hell and last movement’s paradise? Music musics, ultimately, and any narrative parallel fails to fully accommodate those qualities that make the music so extraordinary.

He’s the one, after all, who called his middle movement “Purgatorio,” suggesting the epic scope of Dante’s Divine Comedy and practically begging a listener to look for an Inferno and a Paradisio. Or is it really the middle three movements that function collectively as a kinetic purgatory—a waiting place, an interruption—foil to the first movement’s hell and last movement’s paradise? Music musics, ultimately, and any narrative parallel fails to fully accommodate those qualities that make the music so extraordinary. But this one bears a striking resemblance, I think, to the motive from Richard Strauss’s Salome (1905) that Lawrence Gilman called the ¡¡¡EnTiCeMeNt!!! motive in his 1907 guide to the opera. In isolation, the connection would perhaps merit little attention, but taken with the bass drum hits that open Mahler’s finale and the return of the “poisoned” chord, both of which have parallels in Strauss’s score, I cannot resist the comparison. (It’s the bass drums, remember, that crush Salome with their shields [or something like that], and who can forget the “poisoned” chord when Salome kisses the forbidden fruit, the severed head of Jochanaan?) When Mahler was sketching his Tenth the music of Strauss’s operatic success de scandale was all the rage, and Mahler certainly knew the score well. What’s Mahler doing here? Perhaps he’s contemplating, through music, another recent development in music, in just the same way that the internal scherzos reflect a kind of Schoenbergian shearing of aspects of signification from musical gesture. If Mahler is thinking about Strauss in the finale of his Tenth, the music is too potent, too evocative and immediate not to spark narrative dimensions. What forbidden fruit has Mahler’s symphonic protagonist tasted to be crushed in this way? Whatever it was, Mahler himself didn’t live to taste it. In listening to the last movement, we hear Mahler from beyond the grave, expressing things he did not have the time to express.

But this one bears a striking resemblance, I think, to the motive from Richard Strauss’s Salome (1905) that Lawrence Gilman called the ¡¡¡EnTiCeMeNt!!! motive in his 1907 guide to the opera. In isolation, the connection would perhaps merit little attention, but taken with the bass drum hits that open Mahler’s finale and the return of the “poisoned” chord, both of which have parallels in Strauss’s score, I cannot resist the comparison. (It’s the bass drums, remember, that crush Salome with their shields [or something like that], and who can forget the “poisoned” chord when Salome kisses the forbidden fruit, the severed head of Jochanaan?) When Mahler was sketching his Tenth the music of Strauss’s operatic success de scandale was all the rage, and Mahler certainly knew the score well. What’s Mahler doing here? Perhaps he’s contemplating, through music, another recent development in music, in just the same way that the internal scherzos reflect a kind of Schoenbergian shearing of aspects of signification from musical gesture. If Mahler is thinking about Strauss in the finale of his Tenth, the music is too potent, too evocative and immediate not to spark narrative dimensions. What forbidden fruit has Mahler’s symphonic protagonist tasted to be crushed in this way? Whatever it was, Mahler himself didn’t live to taste it. In listening to the last movement, we hear Mahler from beyond the grave, expressing things he did not have the time to express. Blake (b. 1949) is a dyed-in-the-wool Kiwi: born in Christchurch, educated at Canterbury University, and now Chief Executive of the

Blake (b. 1949) is a dyed-in-the-wool Kiwi: born in Christchurch, educated at Canterbury University, and now Chief Executive of the  The poems are printed in full in the liner notes, and emblazoned across the album art as an epigraph is this quote from the second of them, from which Blake says the music takes its “mood of restlessness”: “Always, in these islands, meeting and parting/Shake us, making tremulous the salt-rimmed air.”

The poems are printed in full in the liner notes, and emblazoned across the album art as an epigraph is this quote from the second of them, from which Blake says the music takes its “mood of restlessness”: “Always, in these islands, meeting and parting/Shake us, making tremulous the salt-rimmed air.” The recent thought-provoking volume The Sea in the British Musical Imagination, edited by

The recent thought-provoking volume The Sea in the British Musical Imagination, edited by  When a descending trumpet figure cuts through the hymn texture, at first it feels like a response to Charles Ives’s Unanswered Question, in which the strings’ slow-moving hymn is cut through by the questioning trumpet. But there’s more to Blake’s trumpet than a dissonant question; as other instruments take up the figure, it reveals itself not as a human but as avian. To wit, the call of the

When a descending trumpet figure cuts through the hymn texture, at first it feels like a response to Charles Ives’s Unanswered Question, in which the strings’ slow-moving hymn is cut through by the questioning trumpet. But there’s more to Blake’s trumpet than a dissonant question; as other instruments take up the figure, it reveals itself not as a human but as avian. To wit, the call of the  The second, while fulfilling its memorial function admirably, also references a special kind of twentieth-century orchestral writing that I think owes a considerable debt to nature documentaries. The final work on the album is also the most recent: The Furnace of Pihanga (1999), inspired by a Maori story about the contest of mountain gods “for the love of the beautiful Pihanga.” There’s a sensitive timbral imagination on display here, and it’s a pleasure to hear Blake tell the story described in his liner notes through the orchestral medium.

The second, while fulfilling its memorial function admirably, also references a special kind of twentieth-century orchestral writing that I think owes a considerable debt to nature documentaries. The final work on the album is also the most recent: The Furnace of Pihanga (1999), inspired by a Maori story about the contest of mountain gods “for the love of the beautiful Pihanga.” There’s a sensitive timbral imagination on display here, and it’s a pleasure to hear Blake tell the story described in his liner notes through the orchestral medium. I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven.

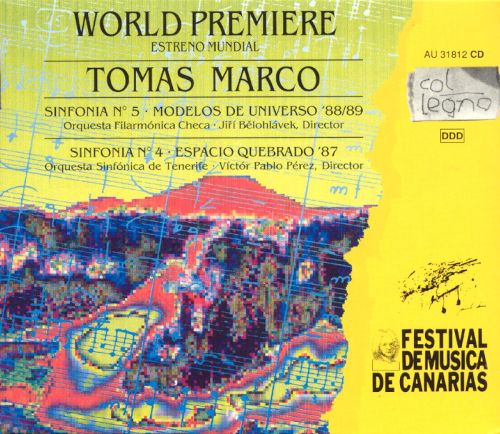

I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven. Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between

Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between  In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.