Mayday! May Day. May 1st. As good a day as any to celebrate beginnings.

Here’s a question for you: What does it mean to write a first symphony? Perhaps for Beethoven it meant self-assertion, a way of setting himself apart from his classical forebears. Perhaps for Brahms it meant living in a world after Beethoven and composing in the company of his by turns inspiring and oppressive ghost. Perhaps for Mahler it meant showing that the symphony had a place in an age of Wagner and Strauss, that it had sufficient epic pull in a concert culture of program music. Perhaps for Bruckner it meant a path toward the divine. Perhaps for Prokofiev and Shostakovich it meant something about returning to the classical origins of the form, reminding a twentieth-century audience that symphonies didn’t have to be hour-long plummetings into the pool of Weltschmerz, although they knew plenty about that. And after the wars? And in the U.S.? Perhaps it came to mean something like. . .self-assertion, at individual and national levels, or living in a world after. . .well, after lots of things—a world of post-ness—or a claim that a first symphony could possess epic pull or was a path to the divine or that it could still manage classical deftness. In fact, it gradually came to mean all those things and more: an overburdened opportunity, and so very irresistible for it, even in a post-symphonic age. I caught the symphonic bug early myself and attempted a three-movement Symphony No. 1, not that anything particularly useful came of it except perhaps an appreciation for composers who could manage it better than I. And it so happens that two fellow San Antonio composers are even now laboring away at symphonies (Brian Bondari, and James Syler, on his second).

(Nexus entry.)

The album I listened to for this entry contains a Symphony No. 1, of course, a work that scored the Pulitzer Prize in 1983. Some of the aims of this particular first symphony are probably similar to those proposed above. Possessed of an immense lyrical wealth akin to late Mahler or Berg or the agonizing side of Shostakovich, it has about it the atmosphere of the epic. At the same time it’s three relatively brief movements taken together clock in at a modest seventeen to eighteen minutes, terser even than most of Papa Haydn’s. The composer (still living) was, as the awarding of the Pulitzer indicates, an American, and here’s where things get more interesting. Does it sound like the great American symphony, and if so, how?

I heard Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s First Symphony long ago as an undergraduate but then hadn’t heard it in the intervening (ahem) years until I recently pulled it from the shelf of the listening library in order to revisit what I understood as an important American work in the genre. Zwilich [pronounced ZWILL-ik] was, after all, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in music, a mighty accomplishment in the early 1980s, which, although it was post-many things, was also pre-many others. I speculate that the prize committee heard in Zwilich’s First something that did sound American to them, not in a flag-waving sense but in a finger-on-the-pulse one, and that they also understood that the composer’s accomplishment represented an important part of the American story, as indeed it did and does.

But the thing that strikes me so powerfully as I return to this symphony is how skillfully Zwilich makes a Euro-American hybrid. I hear the aching strings of Mahler and Berg—she was a violinist first, and it shows—but the texture is far leaner, clear and direct, even Coplandesque at times, primed for effective communication with a larger, American public. In the liner notes for the album, Zwilich explains that she had “long been interested in the elaboration of large-scale works from the initial material.” That might sound like a Schoenbergian way of talking about what happens in symphonic space, but when you listen to the opening of the First Symphony, you hear a major third once, then a second time, then a third time, and that repetition establishes the rising motive that becomes a theme. This strategy—the straightforward communication through repetition of a simple initial idea, a germ, that will give rise to the rest—is more appropriate to Beethoven’s Fifth than to most works with such notable modernist credentials. Mass communication of classical music, like Texaco sponsoring broadcasts from the Met from 1931 to 2003, sounds pretty American, doesn’t it?

But more is needed to make that communication work than the repetition of an ascending major third, however beautifully varied or artfully orchestrated. And Zwilich does give more. The central developmental section of the first movement doesn’t sound like but is informed by melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, and orchestrational logic reminiscent of the action-oriented music of late-1970s and early-1980s big-budget Hollywood film scores. More specifically, I hear the development section as a cousin of John Williams’s score for Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). There’s probably more to say about specific connections between film scores and (latent) narrativity in Zwilich’s symphony. Richard Dyer writes in the liner notes that, despite the fact that the composer usually waits for commissions, she began her First Symphony before she had one, and that the “first fifteen bars,” from which “everything in the work arises,” she felt “compelled to write.” Who knows what lies behind this, what it was that compelled her? But the lyrical language of the work, which moves between anguish and repose, opens the door to the narrative imagination. We needn’t walk through. It’s easy enough to accept Zwilich’s work as “absolute music,” and my suggestion about a certain affinity with contemporaneous film scores is about the materials of music: notes, rhythms, and textures. Moreover, these notes, rhythms, and textures link what was going on in the classical season of orchestras in the late 1970s and 1980s and what was going on (or starting to go on) in the pops season. Finger on the pulse indeed.

(Nexus exit.)

As always, there’s so very much to say. A work like Zwilich’s First Symphony deserves lengthier exposition, a rich and nuanced reading: it is a worthy and wonderful work, and important since Zwilich has to date written four other symphonies. Go listen to it if you haven’t, or listen to it again if you’ve forgotten it. But this album contains two other fine works as well—Prologue and Variations (1984) and Celebration (1984)—all played admirably by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra under John Nelson. Celebration particularly fascinated me on this listening, unmistakably evoking the opening of Mahler’s First Symphony and anticipating the Tarantella movement of Corigliano’s First Symphony. If neither of those works seem particularly celebratory in those places, then you’ll understand something of my fascination with the rhetorical riddle of Zwilich’s title. And discovering for the first time or rediscovering something fascinating is well worth celebrating.

The second track, “Every Little Kiss,” opens with Hornsby’s piano solo—hardly a surprise, as that was sort of how he carved out his unconventional place in the popiverse of the Reagan years. Through repeated background listening I memorized “every little” nuance of that opening solo.

The second track, “Every Little Kiss,” opens with Hornsby’s piano solo—hardly a surprise, as that was sort of how he carved out his unconventional place in the popiverse of the Reagan years. Through repeated background listening I memorized “every little” nuance of that opening solo.

The atmosphere of quotation begetting quotation that Ives inspires seems echoed, therefore, in the link between the NET film and the LPO recording. This quality is brought out in Serebrier’s extensive program notes, which often reference the 1965 première. In the spirit of Ives, I can’t resist a quotation: “I shall never forget that winter morning at Carnegie Hall, when Stokowski had scheduled the first rehearsal of the Ives Fourth. He stared at the music for a long time, then at the orchestra. I had never seen the score, and my heart stopped when he turned to me and said, ‘Maestro, please come and conduct this last movement. I want to hear it.’ After it was all over, my arms and legs still shaking, I complained that I was sightreading. Stokowski’s reply was, ‘So was the orchestra!’” If they were sightreading on that first day, one of the remarkable things about the première was it was especially well prepared: Stokowski asked for (and got) a number of extra rehearsals, underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See the NET documentary at 7:55 for Stokowski’s explanation, delightfully redolent of the absent-minded professor.) But Serebrier’s recording brought with it almost an additional decade of opportunity to live with the work’s challenges and possibilities, and so it inevitably sounds more refined.

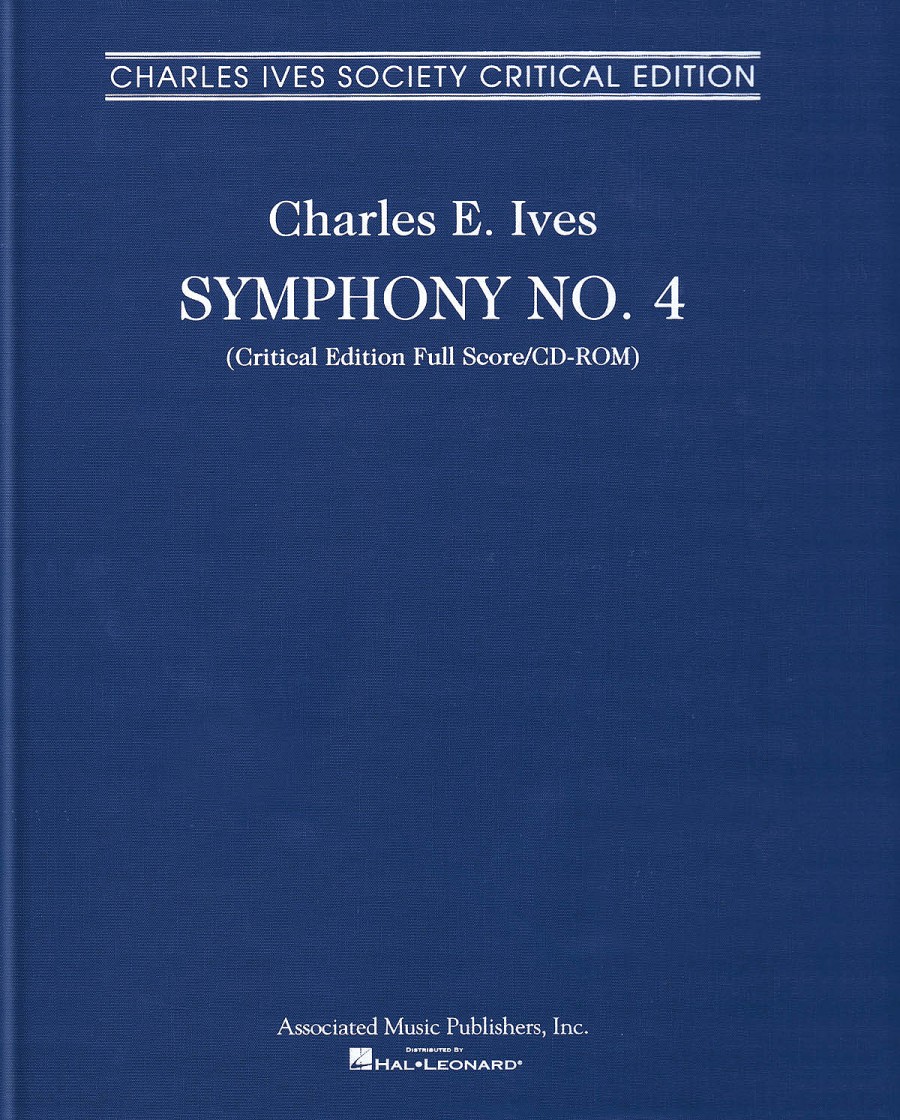

The atmosphere of quotation begetting quotation that Ives inspires seems echoed, therefore, in the link between the NET film and the LPO recording. This quality is brought out in Serebrier’s extensive program notes, which often reference the 1965 première. In the spirit of Ives, I can’t resist a quotation: “I shall never forget that winter morning at Carnegie Hall, when Stokowski had scheduled the first rehearsal of the Ives Fourth. He stared at the music for a long time, then at the orchestra. I had never seen the score, and my heart stopped when he turned to me and said, ‘Maestro, please come and conduct this last movement. I want to hear it.’ After it was all over, my arms and legs still shaking, I complained that I was sightreading. Stokowski’s reply was, ‘So was the orchestra!’” If they were sightreading on that first day, one of the remarkable things about the première was it was especially well prepared: Stokowski asked for (and got) a number of extra rehearsals, underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See the NET documentary at 7:55 for Stokowski’s explanation, delightfully redolent of the absent-minded professor.) But Serebrier’s recording brought with it almost an additional decade of opportunity to live with the work’s challenges and possibilities, and so it inevitably sounds more refined. Still, it is a revelation to listen to Serebrier’s recording while following along with the 2011 Charles Ives Society Critical Edition of the score, with each movement edited by a different scholar from the variety of sometimes conflicting sources. (This extraordinary publication includes a CD-ROM with scans of all of Ives’s manuscript material for the work.) Looking at Wayne D. Shirley’s edition of the fourth movement, for example, shows how much either was excised from or never incorporated into the edition prepared by the staff of the Fleischer Music Collection, used for the 1965 première and the 1974 recording; following the course of almost any single part reveals that much more is possible than got realized under Stokowski or Serebrier. And, well, who can blame them? Ives asks for an entirely different ensemble for each of his four movements, pushing past Richard Strauss into a kind of proto-Gruppen orchestral environment, particularly in the finale. All this in a work of the 1910s and ‘20s. Not that Ives would have recognized the finale in the 2011 Critical Edition as his, per se. As William Brooks brilliantly proposes in the preface to the edition, in the face of the impossibility of creating a single definitive edition of the finale from a multiplicity of sources, “The workable anarchy of Ives’s music is better manifested in his manuscripts than in publications; and it is the manuscripts which you [Who, me?!?!]—through whom Ives’s music sounds—can and should enter. There can be no Ives urtext, no approved edition. In the re-formed world universal access to the manuscripts will bring into being an ever-expanding sphere of visions, performances—‘editions,’ if you will—all shaped for particular times, places, circumstances. I look forward to your contributions.” This quote resonated powerfully with me as I sat there in the stunned aftermath of the last movement, thinking about the beauty of what I heard and the promise of what I didn’t hear but could almost imagine. (More of it is present in other more recent recordings, incidentally.) Could there ever be enough instruments, enough parts to satisfy Ives’s all-encompassing vision? Could there ever be enough refracted and refracting quotations to answer the call? Brooks says no, but he looks forward to a Borges-like infinite gallery of responses. How wonderful to imagine that in writing about it we come to constitute a version of the work.

Still, it is a revelation to listen to Serebrier’s recording while following along with the 2011 Charles Ives Society Critical Edition of the score, with each movement edited by a different scholar from the variety of sometimes conflicting sources. (This extraordinary publication includes a CD-ROM with scans of all of Ives’s manuscript material for the work.) Looking at Wayne D. Shirley’s edition of the fourth movement, for example, shows how much either was excised from or never incorporated into the edition prepared by the staff of the Fleischer Music Collection, used for the 1965 première and the 1974 recording; following the course of almost any single part reveals that much more is possible than got realized under Stokowski or Serebrier. And, well, who can blame them? Ives asks for an entirely different ensemble for each of his four movements, pushing past Richard Strauss into a kind of proto-Gruppen orchestral environment, particularly in the finale. All this in a work of the 1910s and ‘20s. Not that Ives would have recognized the finale in the 2011 Critical Edition as his, per se. As William Brooks brilliantly proposes in the preface to the edition, in the face of the impossibility of creating a single definitive edition of the finale from a multiplicity of sources, “The workable anarchy of Ives’s music is better manifested in his manuscripts than in publications; and it is the manuscripts which you [Who, me?!?!]—through whom Ives’s music sounds—can and should enter. There can be no Ives urtext, no approved edition. In the re-formed world universal access to the manuscripts will bring into being an ever-expanding sphere of visions, performances—‘editions,’ if you will—all shaped for particular times, places, circumstances. I look forward to your contributions.” This quote resonated powerfully with me as I sat there in the stunned aftermath of the last movement, thinking about the beauty of what I heard and the promise of what I didn’t hear but could almost imagine. (More of it is present in other more recent recordings, incidentally.) Could there ever be enough instruments, enough parts to satisfy Ives’s all-encompassing vision? Could there ever be enough refracted and refracting quotations to answer the call? Brooks says no, but he looks forward to a Borges-like infinite gallery of responses. How wonderful to imagine that in writing about it we come to constitute a version of the work. I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven.

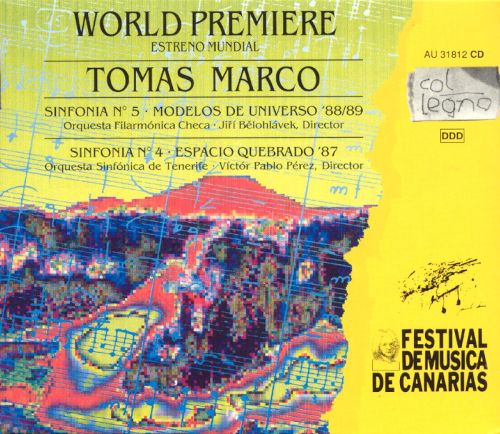

I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven. Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between

Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between  In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

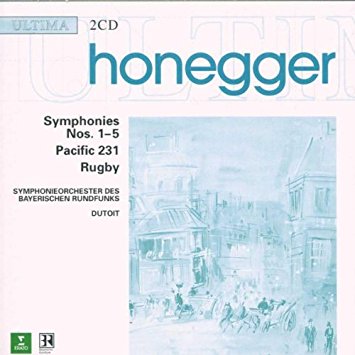

In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) suffered a health crisis in 1947 and did not live too many years beyond that, but he had one more symphony in him. Symphony No. 5 (1950) is subtitled “Di tre re,” with re referring to the note D, which ends every movement. Does this D, with its association with Requiem settings, point to death? Probably so, but to my ears this three-movement work (played here by the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks under Charles Dutoit) also evokes devotion, delight, and defiance, three D-words I’d like to add to describe aspects of the symphony. I hear the first movement as devotion to Honegger’s art and faith. Yes, there is some very sour dissonance in the chorale-like first theme, but the landing places are typically rich extended chords that possess a soaring devotional quality. The climactic trumpet part sounds at once like a plaintive cry to God and a declaration of faith. The second movement is scherzo-like and comparable, in a way, to the third movement of Beethoven’s Fifth, revealing a sense of humor about the human condition. The adagio sections in the movement offer a contrast, perhaps the promise of a soothing afterlife. The third movement is the boldest, and I hear in it a striving for strength, a will to persevere despite any obstacle. I want to cheer the piece on as it raucously unfolds, anchored by assertive brass statements. I don’t feel despair (another D word). I think Honegger knew that music had more to offer and that he had more to leave behind.

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) suffered a health crisis in 1947 and did not live too many years beyond that, but he had one more symphony in him. Symphony No. 5 (1950) is subtitled “Di tre re,” with re referring to the note D, which ends every movement. Does this D, with its association with Requiem settings, point to death? Probably so, but to my ears this three-movement work (played here by the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks under Charles Dutoit) also evokes devotion, delight, and defiance, three D-words I’d like to add to describe aspects of the symphony. I hear the first movement as devotion to Honegger’s art and faith. Yes, there is some very sour dissonance in the chorale-like first theme, but the landing places are typically rich extended chords that possess a soaring devotional quality. The climactic trumpet part sounds at once like a plaintive cry to God and a declaration of faith. The second movement is scherzo-like and comparable, in a way, to the third movement of Beethoven’s Fifth, revealing a sense of humor about the human condition. The adagio sections in the movement offer a contrast, perhaps the promise of a soothing afterlife. The third movement is the boldest, and I hear in it a striving for strength, a will to persevere despite any obstacle. I want to cheer the piece on as it raucously unfolds, anchored by assertive brass statements. I don’t feel despair (another D word). I think Honegger knew that music had more to offer and that he had more to leave behind.