“Well, there’s another completely cool thing I knew nothing about.”

This was my feeling after hearing Tyler Kinnear’s paper on R. Murray Schafer’s The Princess of Stars (1981), an opera that is meant to be performed (and has been several times) on a lake. Hearing excerpts from the work, the sound of a human voice blending with the elements, I could understand how the same person who wrote this music also coined the term soundscape. This music exists as an environment, a particular combination of the concert and natural worlds. Take the natural world away and the piece would lose a central aspect of its identity. During the paper and since, I’ve been thinking about the connection between Schafer’s Princess, part of a twelve-work cycle called Patria, and another late twentieth-century extravaganza of avant-garde opulence, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Licht cycle, which has an opera for each day of the week. I don’t understand the connection at the moment and am resisting the urge to search for it, in part because I think it would require digging into the twelve-part Patria in earnest, and, well. . .so many albums! As a stopgap, though, I determined to seek out all the albums with pieces by R. Murray Schafer (b. 1933) we had in the listening library, to see how they related to the extraordinary noises I heard during Tyler Kinnear’s paper.

The short answer is: There’s no short answer.

The longer answer is:

What a remarkable composer R. Murray Schafer is that he should write something that sounded like that excerpt I heard from The Princess of the Stars and also write the three pieces on the first album I listened to: Flute Concerto (1984), Harp Concerto (1987), and The Darkly Splendid Earth: The Lonely Traveller (1991). I should perhaps say that the third of these pieces is, in the words of the composer, a “double rhapsody for violin and orchestra” – that is, not precisely but almost a concerto, even though it came about in a concerto-like way, as a commission from violinist Jacques Israelievitch. As the title suggests, there are two presences in the soundscape of the piece: the earth itself, sounded by the orchestra, and the traveler, sounded by the violinist. The liner notes to the album (credited to the composer and Robin Elliott) say nothing about the origin of the work’s title, as evocative as it is. I thought perhaps Milton, but a hesitant, wincing peek into the rabbit hole of Google search results yielded only obscure references to Zoroastrianism and to the song “Darkly Splendid World” from British band Current 93’s album Of Ruine or Some Blazing Starre (1993). Perhaps the origin of the title is very obvious, but somehow I doubt the piece’s connection to either of these eyebrow-raising finds, either as descendant or influence.

The other possibility that occurred to me as inspiration for the title was Rousseau’s Meditations of a Solitary Walker (1776-8), which in my mind always suggests Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea (1808-10). Arguably the spirit of Schafer’s double rhapsody is poised between these two works. In Friedrich’s painting, the human is anonymous, voiceless, insignificant in the face of the vast and unknowable. In Rousseau, we are invited to “walk along with” the solitary writer, to trace the steps of his thought as he observes the world. In Friedrich, we never find the human; in Rousseau, we never escape him. Schafer’s violin is in a sense a Rousseau sort of presence, rhapsodizing, yes, in ways virtuosic and expressive, lyrical, fiery – really, in all those ways that we expect the violin to behave in a twentieth-century concerto. The surprise comes with the orchestra’s part of the double rhapsody, which often seems to operate according to entirely different principles. The darkly splendid earth inhabits this soundscape but is not subservient to the traveler in terms of texture or material. Its climaxes need not involve the violin at all, even as an obbligato element, and they need not respect the sovereignty of the soloist by getting out of the way. This is a darkly splendid earth like Friedrich’s rendering of the sea. According to the notes, the unconventional relationship between soloist and orchestra was even more pronounced in the first draft of the piece. I find myself wondering what the experience of it is like in live performance. Does the violinist seem like the monk before the orchestral sea, staring up into the ether to the backdrop of fathomless churning?

The other two pieces on the album would seem to have a much less obvious connection to the Schafer of Princess of the Stars. First, they are called concertos, and each has the traditional three movements. The album notes point out that the Flute Concerto from 1984 was only Schafer’s second work to bear that generic title, the first being the Concerto for Harpsichord and Eight Wind Instruments from 1954. So, after a thirty-year gap, Schafer came back to. . . classical form. This is a different sort of soundscape, maybe not something that Schafer would even identify as such: a sort of soundscape of the mind comprised of an inheritance of works. Here the individual concerto stands in relationship to its own ocean of repertory, which inevitably threatens to subsume any individual concerto. Are we hearing an enactment of genre or a single work? What we hear is, of course, the tension between those two options. I’ll mention just one aspect of each concerto that gripped me, that seemed to claim a certain independence.

In the Flute Concerto, this happened in the slow second movement, by far the longest of the three. The album notes point out that the movement “uses microtonal pitch inflections in imitation of [Asian] music.” Nothing more specific than that. But in the cadenza at the very end of the work, the flute (played by Robert Aitken, who commissioned the work) unmistakably evokes the shakuhachi, a sound that the listener has not been prepared for in any specific way but that points to an important source of extended techniques for the contemporary flutist – i.e., world flutes – and to the international and arguably intercultural orientation of avant-garde music in the last quarter of the twentieth century and beyond.

In the Harp Concerto, what gripped me was the identity of the principal motive that runs through the entire work. (Nexus entry.) I think it’s difficult to ignore that the motive powerfully resembles the one that opens the concluding March from Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber (1943). Could this possibly be a coincidence? Given the popularity of Hindemith’s work, I don’t see how. That other evocations seem to be scattered through the work – echoes of Bartók, Britten, Beethoven, possibly of Berlioz – suggests that the weight of the concert inheritance was very much on Schafer’s mind when writing the work. It is such an attractive work, but it’s hard to conceive that this is the composer of the opera on the lake. Perhaps Schafer is simply supremely good at wearing different hats. Or perhaps the symphonic repertory itself is functioning as a sort of environment that soloist and ensemble inhabit and traverse. It is their darkly splendid earth. (Nexus exit.) However conceived, the concerto seems to have been a useful form for Schafer to continue to explore the relationship between the individual voice and that voice’s inevitable participation in a larger soundscape. And now Patria’s on my ever larger listening list. . .

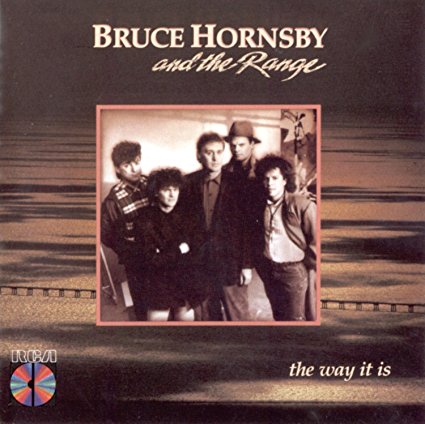

The second track, “Every Little Kiss,” opens with Hornsby’s piano solo—hardly a surprise, as that was sort of how he carved out his unconventional place in the popiverse of the Reagan years. Through repeated background listening I memorized “every little” nuance of that opening solo.

The second track, “Every Little Kiss,” opens with Hornsby’s piano solo—hardly a surprise, as that was sort of how he carved out his unconventional place in the popiverse of the Reagan years. Through repeated background listening I memorized “every little” nuance of that opening solo.

The atmosphere of quotation begetting quotation that Ives inspires seems echoed, therefore, in the link between the NET film and the LPO recording. This quality is brought out in Serebrier’s extensive program notes, which often reference the 1965 première. In the spirit of Ives, I can’t resist a quotation: “I shall never forget that winter morning at Carnegie Hall, when Stokowski had scheduled the first rehearsal of the Ives Fourth. He stared at the music for a long time, then at the orchestra. I had never seen the score, and my heart stopped when he turned to me and said, ‘Maestro, please come and conduct this last movement. I want to hear it.’ After it was all over, my arms and legs still shaking, I complained that I was sightreading. Stokowski’s reply was, ‘So was the orchestra!’” If they were sightreading on that first day, one of the remarkable things about the première was it was especially well prepared: Stokowski asked for (and got) a number of extra rehearsals, underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See the NET documentary at 7:55 for Stokowski’s explanation, delightfully redolent of the absent-minded professor.) But Serebrier’s recording brought with it almost an additional decade of opportunity to live with the work’s challenges and possibilities, and so it inevitably sounds more refined.

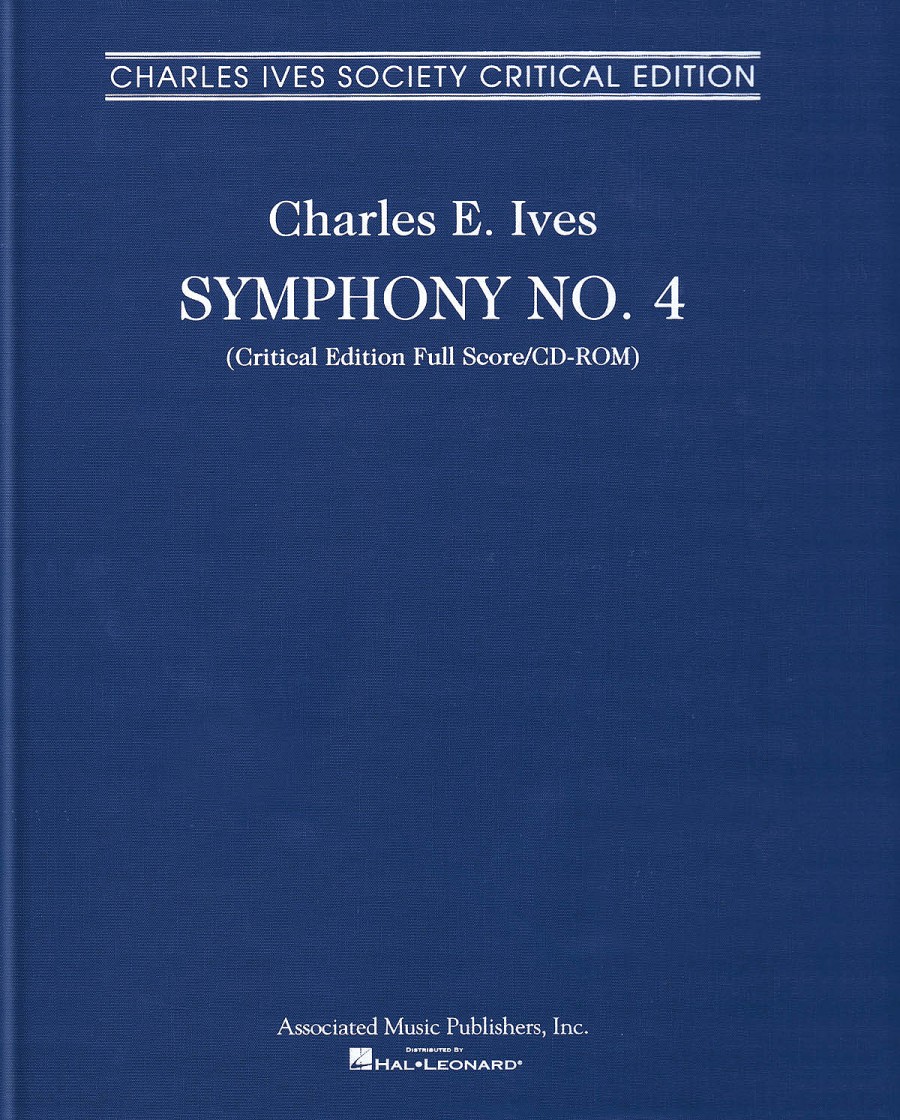

The atmosphere of quotation begetting quotation that Ives inspires seems echoed, therefore, in the link between the NET film and the LPO recording. This quality is brought out in Serebrier’s extensive program notes, which often reference the 1965 première. In the spirit of Ives, I can’t resist a quotation: “I shall never forget that winter morning at Carnegie Hall, when Stokowski had scheduled the first rehearsal of the Ives Fourth. He stared at the music for a long time, then at the orchestra. I had never seen the score, and my heart stopped when he turned to me and said, ‘Maestro, please come and conduct this last movement. I want to hear it.’ After it was all over, my arms and legs still shaking, I complained that I was sightreading. Stokowski’s reply was, ‘So was the orchestra!’” If they were sightreading on that first day, one of the remarkable things about the première was it was especially well prepared: Stokowski asked for (and got) a number of extra rehearsals, underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See the NET documentary at 7:55 for Stokowski’s explanation, delightfully redolent of the absent-minded professor.) But Serebrier’s recording brought with it almost an additional decade of opportunity to live with the work’s challenges and possibilities, and so it inevitably sounds more refined. Still, it is a revelation to listen to Serebrier’s recording while following along with the 2011 Charles Ives Society Critical Edition of the score, with each movement edited by a different scholar from the variety of sometimes conflicting sources. (This extraordinary publication includes a CD-ROM with scans of all of Ives’s manuscript material for the work.) Looking at Wayne D. Shirley’s edition of the fourth movement, for example, shows how much either was excised from or never incorporated into the edition prepared by the staff of the Fleischer Music Collection, used for the 1965 première and the 1974 recording; following the course of almost any single part reveals that much more is possible than got realized under Stokowski or Serebrier. And, well, who can blame them? Ives asks for an entirely different ensemble for each of his four movements, pushing past Richard Strauss into a kind of proto-Gruppen orchestral environment, particularly in the finale. All this in a work of the 1910s and ‘20s. Not that Ives would have recognized the finale in the 2011 Critical Edition as his, per se. As William Brooks brilliantly proposes in the preface to the edition, in the face of the impossibility of creating a single definitive edition of the finale from a multiplicity of sources, “The workable anarchy of Ives’s music is better manifested in his manuscripts than in publications; and it is the manuscripts which you [Who, me?!?!]—through whom Ives’s music sounds—can and should enter. There can be no Ives urtext, no approved edition. In the re-formed world universal access to the manuscripts will bring into being an ever-expanding sphere of visions, performances—‘editions,’ if you will—all shaped for particular times, places, circumstances. I look forward to your contributions.” This quote resonated powerfully with me as I sat there in the stunned aftermath of the last movement, thinking about the beauty of what I heard and the promise of what I didn’t hear but could almost imagine. (More of it is present in other more recent recordings, incidentally.) Could there ever be enough instruments, enough parts to satisfy Ives’s all-encompassing vision? Could there ever be enough refracted and refracting quotations to answer the call? Brooks says no, but he looks forward to a Borges-like infinite gallery of responses. How wonderful to imagine that in writing about it we come to constitute a version of the work.

Still, it is a revelation to listen to Serebrier’s recording while following along with the 2011 Charles Ives Society Critical Edition of the score, with each movement edited by a different scholar from the variety of sometimes conflicting sources. (This extraordinary publication includes a CD-ROM with scans of all of Ives’s manuscript material for the work.) Looking at Wayne D. Shirley’s edition of the fourth movement, for example, shows how much either was excised from or never incorporated into the edition prepared by the staff of the Fleischer Music Collection, used for the 1965 première and the 1974 recording; following the course of almost any single part reveals that much more is possible than got realized under Stokowski or Serebrier. And, well, who can blame them? Ives asks for an entirely different ensemble for each of his four movements, pushing past Richard Strauss into a kind of proto-Gruppen orchestral environment, particularly in the finale. All this in a work of the 1910s and ‘20s. Not that Ives would have recognized the finale in the 2011 Critical Edition as his, per se. As William Brooks brilliantly proposes in the preface to the edition, in the face of the impossibility of creating a single definitive edition of the finale from a multiplicity of sources, “The workable anarchy of Ives’s music is better manifested in his manuscripts than in publications; and it is the manuscripts which you [Who, me?!?!]—through whom Ives’s music sounds—can and should enter. There can be no Ives urtext, no approved edition. In the re-formed world universal access to the manuscripts will bring into being an ever-expanding sphere of visions, performances—‘editions,’ if you will—all shaped for particular times, places, circumstances. I look forward to your contributions.” This quote resonated powerfully with me as I sat there in the stunned aftermath of the last movement, thinking about the beauty of what I heard and the promise of what I didn’t hear but could almost imagine. (More of it is present in other more recent recordings, incidentally.) Could there ever be enough instruments, enough parts to satisfy Ives’s all-encompassing vision? Could there ever be enough refracted and refracting quotations to answer the call? Brooks says no, but he looks forward to a Borges-like infinite gallery of responses. How wonderful to imagine that in writing about it we come to constitute a version of the work. The recording I was listening to, incidentally, was of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales under Mark Wigglesworth, which accompanied the August 1994 issue of BBC Music. In some ways it makes a great deal of sense to listen to this live performance, as the 1964 concert that brought the fully realized Tenth to the world was part of that season’s Proms.

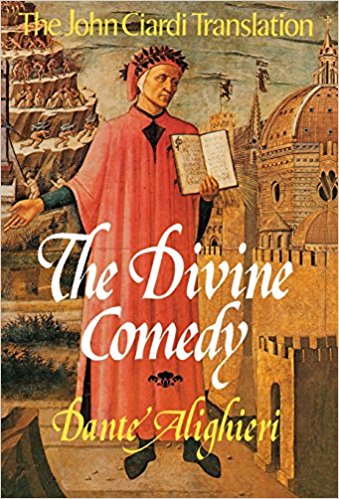

The recording I was listening to, incidentally, was of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales under Mark Wigglesworth, which accompanied the August 1994 issue of BBC Music. In some ways it makes a great deal of sense to listen to this live performance, as the 1964 concert that brought the fully realized Tenth to the world was part of that season’s Proms. He’s the one, after all, who called his middle movement “Purgatorio,” suggesting the epic scope of Dante’s Divine Comedy and practically begging a listener to look for an Inferno and a Paradisio. Or is it really the middle three movements that function collectively as a kinetic purgatory—a waiting place, an interruption—foil to the first movement’s hell and last movement’s paradise? Music musics, ultimately, and any narrative parallel fails to fully accommodate those qualities that make the music so extraordinary.

He’s the one, after all, who called his middle movement “Purgatorio,” suggesting the epic scope of Dante’s Divine Comedy and practically begging a listener to look for an Inferno and a Paradisio. Or is it really the middle three movements that function collectively as a kinetic purgatory—a waiting place, an interruption—foil to the first movement’s hell and last movement’s paradise? Music musics, ultimately, and any narrative parallel fails to fully accommodate those qualities that make the music so extraordinary. But this one bears a striking resemblance, I think, to the motive from Richard Strauss’s Salome (1905) that Lawrence Gilman called the ¡¡¡EnTiCeMeNt!!! motive in his 1907 guide to the opera. In isolation, the connection would perhaps merit little attention, but taken with the bass drum hits that open Mahler’s finale and the return of the “poisoned” chord, both of which have parallels in Strauss’s score, I cannot resist the comparison. (It’s the bass drums, remember, that crush Salome with their shields [or something like that], and who can forget the “poisoned” chord when Salome kisses the forbidden fruit, the severed head of Jochanaan?) When Mahler was sketching his Tenth the music of Strauss’s operatic success de scandale was all the rage, and Mahler certainly knew the score well. What’s Mahler doing here? Perhaps he’s contemplating, through music, another recent development in music, in just the same way that the internal scherzos reflect a kind of Schoenbergian shearing of aspects of signification from musical gesture. If Mahler is thinking about Strauss in the finale of his Tenth, the music is too potent, too evocative and immediate not to spark narrative dimensions. What forbidden fruit has Mahler’s symphonic protagonist tasted to be crushed in this way? Whatever it was, Mahler himself didn’t live to taste it. In listening to the last movement, we hear Mahler from beyond the grave, expressing things he did not have the time to express.

But this one bears a striking resemblance, I think, to the motive from Richard Strauss’s Salome (1905) that Lawrence Gilman called the ¡¡¡EnTiCeMeNt!!! motive in his 1907 guide to the opera. In isolation, the connection would perhaps merit little attention, but taken with the bass drum hits that open Mahler’s finale and the return of the “poisoned” chord, both of which have parallels in Strauss’s score, I cannot resist the comparison. (It’s the bass drums, remember, that crush Salome with their shields [or something like that], and who can forget the “poisoned” chord when Salome kisses the forbidden fruit, the severed head of Jochanaan?) When Mahler was sketching his Tenth the music of Strauss’s operatic success de scandale was all the rage, and Mahler certainly knew the score well. What’s Mahler doing here? Perhaps he’s contemplating, through music, another recent development in music, in just the same way that the internal scherzos reflect a kind of Schoenbergian shearing of aspects of signification from musical gesture. If Mahler is thinking about Strauss in the finale of his Tenth, the music is too potent, too evocative and immediate not to spark narrative dimensions. What forbidden fruit has Mahler’s symphonic protagonist tasted to be crushed in this way? Whatever it was, Mahler himself didn’t live to taste it. In listening to the last movement, we hear Mahler from beyond the grave, expressing things he did not have the time to express. Honegger’s Rugby, a piece inspired by that sport, would seem to represent an unusual phenomenon in art music. My search to find similar pieces has revealed that there are not many that relate directly to a sport or a game. (I welcome readers to add to my initial list!) Stravinsky wrote Jeu de cartes, for example, which of course deals (no pun intended) with a card game. Honegger may have been inspired by Debussy, whose Jeux features an attempt to connect musical rhythm with a bouncing tennis ball. However, Jeux is not directly inspired by the game of tennis. That most eccentric French composer, Erik Satie, did write Sports et Divertissements for piano solo, but the only actual sports subjects in the work are tennis and golf (unless you think Satie thought of yachting and fishing as sports). Bohuslav Martinů composed Half-Time, inspired by football (soccer). (Bateman 2015) I am not sure whether Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1908) should be counted as another example, since it’s mostly about watching the game (and eating at it), but even if it is, there are not that many popular songs that turn sports into music.

Honegger’s Rugby, a piece inspired by that sport, would seem to represent an unusual phenomenon in art music. My search to find similar pieces has revealed that there are not many that relate directly to a sport or a game. (I welcome readers to add to my initial list!) Stravinsky wrote Jeu de cartes, for example, which of course deals (no pun intended) with a card game. Honegger may have been inspired by Debussy, whose Jeux features an attempt to connect musical rhythm with a bouncing tennis ball. However, Jeux is not directly inspired by the game of tennis. That most eccentric French composer, Erik Satie, did write Sports et Divertissements for piano solo, but the only actual sports subjects in the work are tennis and golf (unless you think Satie thought of yachting and fishing as sports). Bohuslav Martinů composed Half-Time, inspired by football (soccer). (Bateman 2015) I am not sure whether Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1908) should be counted as another example, since it’s mostly about watching the game (and eating at it), but even if it is, there are not that many popular songs that turn sports into music. Or do I go in another direction entirely and talk about the uses of Wagner—for example, the use of the Prelude from Das Rheingold in Terrence Malick’s film The New World (2005), ostensibly about the founding of Jamestown and the relationship of John Smith and Pocahontas, but projected, through the use of Wagner’s Prelude, into a larger creation myth, an originating legend for America paralleling the creation of Wagner’s world of the Ring, and/or a suggestion of the unspoiled world before European colonization.

Or do I go in another direction entirely and talk about the uses of Wagner—for example, the use of the Prelude from Das Rheingold in Terrence Malick’s film The New World (2005), ostensibly about the founding of Jamestown and the relationship of John Smith and Pocahontas, but projected, through the use of Wagner’s Prelude, into a larger creation myth, an originating legend for America paralleling the creation of Wagner’s world of the Ring, and/or a suggestion of the unspoiled world before European colonization. I take consolation from reading Deryck Cooke’s I Saw the World End: A Study of Wagner’s Ring (Oxford University Press, 1979). An attempt to say as much as could be said, Cooke managed to say intriguing things about the libretti (and occasionally the music) for the first two Ring operas, and then laid him down to rest. Somehow this is touchingly fitting, in a way that echoes other extraordinary projects of scholarship cut short by the unsympathetic winnower: Henry-Louis de La Grange’s revision of his definitive Mahler biography, J. A. B. van Buitenen’s translation of the Mahabharata. What I mean is that the epic subject is honored, in a sense, by not being fully encompassed by similarly epic scholarship. On a more pedestrian level, I was by turns upset, amused, and relieved that in the extensive liner notes + libretto accompanying Karajan’s classic recording of Das Rheingold with the Berlin Philharmonic, the essayist Wolfram Schwinger hardly mentions that singing is going on. (Yes, really!) Schwinger’s focus is almost exclusively on the Master—Karajan!—and his sensitivity to orchestration, his commitment to accuracy, transparency, his refusal to get bogged down and insistence on maintaining forward momentum. All well and good, but. . .singers?

I take consolation from reading Deryck Cooke’s I Saw the World End: A Study of Wagner’s Ring (Oxford University Press, 1979). An attempt to say as much as could be said, Cooke managed to say intriguing things about the libretti (and occasionally the music) for the first two Ring operas, and then laid him down to rest. Somehow this is touchingly fitting, in a way that echoes other extraordinary projects of scholarship cut short by the unsympathetic winnower: Henry-Louis de La Grange’s revision of his definitive Mahler biography, J. A. B. van Buitenen’s translation of the Mahabharata. What I mean is that the epic subject is honored, in a sense, by not being fully encompassed by similarly epic scholarship. On a more pedestrian level, I was by turns upset, amused, and relieved that in the extensive liner notes + libretto accompanying Karajan’s classic recording of Das Rheingold with the Berlin Philharmonic, the essayist Wolfram Schwinger hardly mentions that singing is going on. (Yes, really!) Schwinger’s focus is almost exclusively on the Master—Karajan!—and his sensitivity to orchestration, his commitment to accuracy, transparency, his refusal to get bogged down and insistence on maintaining forward momentum. All well and good, but. . .singers? After all, here is Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Wotan, the ultimate singer of German Lieder crafting a father of the gods who is lyrical and sympathetic instead of brash, spoiled, tyrannical. And here is the masterful performance of Gerhard Stolze as Loge, who follows every opportunity for multi-dimensionality of character that Wagner provides: at one moment playfully mercurial, at another fiercely scornful, at another distant and wise. And here is Martti Talvela as Fasolt, volleying blasts of bass sonority over the orchestra and hamming it up marvelously as the unlikely love-struck giant. But perhaps this is why Schwinger doesn’t say much about the singers—they do their job splendidly, on the whole, so his focus is free to flit to other phenomena. (How’s that for Stabreim?) All this to say that, after delay and uncertainty, I feel liberated not to attempt the completist’s gambit. Flit, float, fleetly flee, fly—it will be enough to be and not to be enough.

After all, here is Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Wotan, the ultimate singer of German Lieder crafting a father of the gods who is lyrical and sympathetic instead of brash, spoiled, tyrannical. And here is the masterful performance of Gerhard Stolze as Loge, who follows every opportunity for multi-dimensionality of character that Wagner provides: at one moment playfully mercurial, at another fiercely scornful, at another distant and wise. And here is Martti Talvela as Fasolt, volleying blasts of bass sonority over the orchestra and hamming it up marvelously as the unlikely love-struck giant. But perhaps this is why Schwinger doesn’t say much about the singers—they do their job splendidly, on the whole, so his focus is free to flit to other phenomena. (How’s that for Stabreim?) All this to say that, after delay and uncertainty, I feel liberated not to attempt the completist’s gambit. Flit, float, fleetly flee, fly—it will be enough to be and not to be enough. (Don’t say anything about Tolkien. . .don’t say it!!! No, go on and say it—you’re in the nexus!)

(Don’t say anything about Tolkien. . .don’t say it!!! No, go on and say it—you’re in the nexus!) Wagner invites us to consider, though, what might have happened had one of the Rhinemaidens chimed, “Oh, so he doesn’t replace the toilet paper and puts his elbows on the table—can’t help lovin’ that dwarf of mine!” And how does he invite us to consider this possibility? By writing mock-love music, of course! The Rhinemaidens sing, each of them, as if they’ve fallen for our sulfurous cave-dweller, and he buys it each time. But we know better, and not just because of the narrative context. Wagner hams it up, giving us saccharine overtures interrupted by action-oriented “underscore.” (Incidentally, do you realize how much mickey-mousing there is in Das Rheingold?! Steamboat Willie, sit down!) The music shifts gears too quickly for us to hear the love music as genuine; something that gets that sticky that quickly must be manufactured.

Wagner invites us to consider, though, what might have happened had one of the Rhinemaidens chimed, “Oh, so he doesn’t replace the toilet paper and puts his elbows on the table—can’t help lovin’ that dwarf of mine!” And how does he invite us to consider this possibility? By writing mock-love music, of course! The Rhinemaidens sing, each of them, as if they’ve fallen for our sulfurous cave-dweller, and he buys it each time. But we know better, and not just because of the narrative context. Wagner hams it up, giving us saccharine overtures interrupted by action-oriented “underscore.” (Incidentally, do you realize how much mickey-mousing there is in Das Rheingold?! Steamboat Willie, sit down!) The music shifts gears too quickly for us to hear the love music as genuine; something that gets that sticky that quickly must be manufactured. Wagner was the kind of brilliant orchestrator who understood the cultural significance of timbre, particularly as it had been used historically in opera, and knew therefore how to use timbre to communicate dramatic ideas. But the world of the Ring seems to me to have presented Wagner with the perhaps singular opportunity to associate instruments with primal elements. Okay, so this idea is partly formed at best, but I’m recording it nonetheless as one of those topics to keep in mind as the life journey that constitutes anything more than a passing familiarity with Wagner’s Ring continues to unfold. Long may it last and never reach its end.

Wagner was the kind of brilliant orchestrator who understood the cultural significance of timbre, particularly as it had been used historically in opera, and knew therefore how to use timbre to communicate dramatic ideas. But the world of the Ring seems to me to have presented Wagner with the perhaps singular opportunity to associate instruments with primal elements. Okay, so this idea is partly formed at best, but I’m recording it nonetheless as one of those topics to keep in mind as the life journey that constitutes anything more than a passing familiarity with Wagner’s Ring continues to unfold. Long may it last and never reach its end. Here’s the strange assignment I set myself. To listen critically to the late music of Lord Berners (1883-1950), the “last eccentric,” the “English Satie.” Friend of Stravinsky—you can read their published correspondence!—diplomat in the foreign service from 1909-20, painter whose exhibitions graced London’s Reid and Lefevre Galleries, novelist and autobiographer. Oh, and ¡¡¡LoRd!!!, by Jove. If you want a taste of the sort of thing at which his lordship excelled, give ear to the ballet suite from The Triumph of Neptune (1926) in

Here’s the strange assignment I set myself. To listen critically to the late music of Lord Berners (1883-1950), the “last eccentric,” the “English Satie.” Friend of Stravinsky—you can read their published correspondence!—diplomat in the foreign service from 1909-20, painter whose exhibitions graced London’s Reid and Lefevre Galleries, novelist and autobiographer. Oh, and ¡¡¡LoRd!!!, by Jove. If you want a taste of the sort of thing at which his lordship excelled, give ear to the ballet suite from The Triumph of Neptune (1926) in  And how could I ever convince anyone of such a claim?

And how could I ever convince anyone of such a claim? Not difficult at all, though, or at least not emotionally dishonest, to affectionately craft a sort of pastiche-synthesis from the sounds of that loved and lost prewar world. Lane writes in his liner notes that Les sirènes, the first new work given by Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Covent Garden, by one of the only two Brits ever commissioned by Diaghilev, was “not a success,” “deemed to have been have out of touch with the times.” What does that mean, I wonder. I can’t help but think of the sound and character of Peter Grimes, which had its première at Sadler’s Wells the year before Les sirènes (albeit at a different location). It’s hard to think of the two works inhabiting the same two years, much less the same city, all while sharing the name Sadler’s Wells. The world was indeed changing.

Not difficult at all, though, or at least not emotionally dishonest, to affectionately craft a sort of pastiche-synthesis from the sounds of that loved and lost prewar world. Lane writes in his liner notes that Les sirènes, the first new work given by Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Covent Garden, by one of the only two Brits ever commissioned by Diaghilev, was “not a success,” “deemed to have been have out of touch with the times.” What does that mean, I wonder. I can’t help but think of the sound and character of Peter Grimes, which had its première at Sadler’s Wells the year before Les sirènes (albeit at a different location). It’s hard to think of the two works inhabiting the same two years, much less the same city, all while sharing the name Sadler’s Wells. The world was indeed changing. This disc of late Berners also includes the suite from his ballet Cupid and Psyche (1938), which displays just as much craft, shares with Les sirènes a delight in dance and dated national styles (Viennese waltz, “Spanish” music through a Parisian fin-de-siècle filter, the occasional touch of Offenbach or Tchaikovsky). My favorite moment is the Entr’acte, which apparently depicts Psyche in her custom-made palace, where “she lives happily awhile.” The music is atmospheric, placid, suggesting a place outside of time. The flute solo that flits over the top of the gently rolling texture cleverly calls to mind another placid Entr’acte with a flute solo, the one from Carmen. The other piece on the disc, Caprice Péruvien, was arranged by Constant Lambert from Berners’s opera Le carrosse du Saint Sacrement (1923). It’s generally an essay in the “Spanish” mode so loved by early twentieth-century French composers, but without the strange magic of, say, Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole. It’s a bit of a task both to shake one’s perception of the nonsensical use of this idiom for the story of a commedia dell’arte troupe in eighteenth-century Peru and to forgive the music for not being Ravel, but if one can do all that, Berners’s undeniable fluency and apparent delight in writing in familiar idioms come through.

This disc of late Berners also includes the suite from his ballet Cupid and Psyche (1938), which displays just as much craft, shares with Les sirènes a delight in dance and dated national styles (Viennese waltz, “Spanish” music through a Parisian fin-de-siècle filter, the occasional touch of Offenbach or Tchaikovsky). My favorite moment is the Entr’acte, which apparently depicts Psyche in her custom-made palace, where “she lives happily awhile.” The music is atmospheric, placid, suggesting a place outside of time. The flute solo that flits over the top of the gently rolling texture cleverly calls to mind another placid Entr’acte with a flute solo, the one from Carmen. The other piece on the disc, Caprice Péruvien, was arranged by Constant Lambert from Berners’s opera Le carrosse du Saint Sacrement (1923). It’s generally an essay in the “Spanish” mode so loved by early twentieth-century French composers, but without the strange magic of, say, Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole. It’s a bit of a task both to shake one’s perception of the nonsensical use of this idiom for the story of a commedia dell’arte troupe in eighteenth-century Peru and to forgive the music for not being Ravel, but if one can do all that, Berners’s undeniable fluency and apparent delight in writing in familiar idioms come through.![Handel-Alcina-Bonynge-5a[London-3LP].jpg](https://soundtrove.blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/handel-alcina-bonynge-5alondon-3lp2.jpg)

“Bali-Ha’i” is pretty convincing in this role; Rodgers achieves a suggestion of the mysterious, romantic allure of island vistas in a way that perhaps parallels the suggestion of the beauty of the mountains in the opening of The Sound of Music. But what about Bloody Mary’s other song, “

“Bali-Ha’i” is pretty convincing in this role; Rodgers achieves a suggestion of the mysterious, romantic allure of island vistas in a way that perhaps parallels the suggestion of the beauty of the mountains in the opening of The Sound of Music. But what about Bloody Mary’s other song, “ And what about Handel’s music for Alcina? She also has her “Bali Ha’i” moment in her first aria, “

And what about Handel’s music for Alcina? She also has her “Bali Ha’i” moment in her first aria, “ Another reason we can accept La Stupenda’s humiliation and defeat is that Alcina isn’t always such a nice person. In Act III, in a final act of tigress-like desperation, she eggs on Oberto, a captive boy whom she allowed to remain human instead of turning into a beast, to kill a lion that approaches him. Oberto (Mirella Freni!) realizes that the lion is actually his father—in part because the lion nuzzles up to him—and calls Alcina, whom he had previously thought of as protector and friend, “Barbara!” (“Barbarous one!”) This is the real end of her world of enchantment. It makes me think of the moment at the end of Spirited Away (千と千尋の神隠し, 2001) when Yubāba asks Chihiro to choose which pair of swine is actually her transformed parents as a last test before she will return her real name and release her from the kingdom of the spirits. (It’s a trap, but one Chihiro, like Oberto [and Admiral Ackbar], sees through.)

Another reason we can accept La Stupenda’s humiliation and defeat is that Alcina isn’t always such a nice person. In Act III, in a final act of tigress-like desperation, she eggs on Oberto, a captive boy whom she allowed to remain human instead of turning into a beast, to kill a lion that approaches him. Oberto (Mirella Freni!) realizes that the lion is actually his father—in part because the lion nuzzles up to him—and calls Alcina, whom he had previously thought of as protector and friend, “Barbara!” (“Barbarous one!”) This is the real end of her world of enchantment. It makes me think of the moment at the end of Spirited Away (千と千尋の神隠し, 2001) when Yubāba asks Chihiro to choose which pair of swine is actually her transformed parents as a last test before she will return her real name and release her from the kingdom of the spirits. (It’s a trap, but one Chihiro, like Oberto [and Admiral Ackbar], sees through.) As Winton Dean writes in his magnificent Handel’s Operas, 1726-1741, this trio, a phenomenon “all too rare in Handel’s operas. . .stands beside those in Tamerlano and Orlando as a masterly summing up of a dramatic confrontation.” <1> And then? Well, then Alcina is utterly defeated, her magic urn broken, all her enchantments undone. The chorus of former rocks, waves, and beasts sings about their release “from the blind horror of night” (“Dall’orror di notte cieca”). It feels like the prisoners’ stepping into the light of the courtyard in Fidelio, like the broadcasting of the Letter Duet from Figaro over the loudspeakers in Shawshank Redemption. Winton Dean talks about Act III of Alcina as “trac[ing] the disintegration of Alcina’s personality.” How far she had to fall from the vocal heights of her first Act I aria!

As Winton Dean writes in his magnificent Handel’s Operas, 1726-1741, this trio, a phenomenon “all too rare in Handel’s operas. . .stands beside those in Tamerlano and Orlando as a masterly summing up of a dramatic confrontation.” <1> And then? Well, then Alcina is utterly defeated, her magic urn broken, all her enchantments undone. The chorus of former rocks, waves, and beasts sings about their release “from the blind horror of night” (“Dall’orror di notte cieca”). It feels like the prisoners’ stepping into the light of the courtyard in Fidelio, like the broadcasting of the Letter Duet from Figaro over the loudspeakers in Shawshank Redemption. Winton Dean talks about Act III of Alcina as “trac[ing] the disintegration of Alcina’s personality.” How far she had to fall from the vocal heights of her first Act I aria! The role of Bloody Mary, mother of Liat, the Tonkinese love interest of American Lt. Joseph Cable, was played in both the original Broadway production and the 1958 film by Juanita Hall. I’m listening to the original Broadway cast recording, one of the joys of which is reading the album notes, so here’s what the notes say about Hall: “. . .formerly was associated with the Hall Johnson Choir as soloist and as associate director. She later founded the Juanita Hall Choir.” Hall (1901-68), born in New Jersey and eventually trained at Juilliard, was also an African American, but when Richard Rodgers heard her, he wanted her cast in the role of the Tonkinese mother (and, later, in the role of Madam Liang in Flower Drum Song).

The role of Bloody Mary, mother of Liat, the Tonkinese love interest of American Lt. Joseph Cable, was played in both the original Broadway production and the 1958 film by Juanita Hall. I’m listening to the original Broadway cast recording, one of the joys of which is reading the album notes, so here’s what the notes say about Hall: “. . .formerly was associated with the Hall Johnson Choir as soloist and as associate director. She later founded the Juanita Hall Choir.” Hall (1901-68), born in New Jersey and eventually trained at Juilliard, was also an African American, but when Richard Rodgers heard her, he wanted her cast in the role of the Tonkinese mother (and, later, in the role of Madam Liang in Flower Drum Song). Consider some of the layers of racial politics here: those embedded in the source material for the story—that is, American soldiers’ experiences in South Asia during and after the Second World War; those found in James Michener’s Tales of the South Pacific, the source for the musical; those found in Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan’s adaptation; those found in the casting of the Broadway production of South Pacific; those found in the writing and casting of the 1958 film; our own in 2018. We can’t untangle it. It’s a mess. It seems clear that by casting an African American for a major Broadway production at a time when Broadway was segregated, Rodgers and others thought of themselves as activists to some extent. Beyond that simple point, pursuing the tale of appropriation, misrepresentation, and racial in/justice represented by South Pacific looks a pretty bewildering enterprise, so much so that we might do well to forsake the whole thing were it not for. . .

Consider some of the layers of racial politics here: those embedded in the source material for the story—that is, American soldiers’ experiences in South Asia during and after the Second World War; those found in James Michener’s Tales of the South Pacific, the source for the musical; those found in Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan’s adaptation; those found in the casting of the Broadway production of South Pacific; those found in the writing and casting of the 1958 film; our own in 2018. We can’t untangle it. It’s a mess. It seems clear that by casting an African American for a major Broadway production at a time when Broadway was segregated, Rodgers and others thought of themselves as activists to some extent. Beyond that simple point, pursuing the tale of appropriation, misrepresentation, and racial in/justice represented by South Pacific looks a pretty bewildering enterprise, so much so that we might do well to forsake the whole thing were it not for. . . In some ways that’s unfair to Carmen and Butterfly. Both feature male protagonists who are deeply troubled. Don José, violent and jealous, ends up winning few friends in the audience when he murders the object of his desire; Pinkerton, selfish and ignorant, similarly makes himself a villain by leaving Cio-Cio-san in a situation where suicide is her best option. The men are not unsullied heroes; they’re weak and small and make life worse for others. So in a sense the longing called up by Bizet and Puccini in Carmen and Butterfly is shown to be a fruitless creation of witless men, their untutored desire a path to destruction that calls into question the entire exotic mode.

In some ways that’s unfair to Carmen and Butterfly. Both feature male protagonists who are deeply troubled. Don José, violent and jealous, ends up winning few friends in the audience when he murders the object of his desire; Pinkerton, selfish and ignorant, similarly makes himself a villain by leaving Cio-Cio-san in a situation where suicide is her best option. The men are not unsullied heroes; they’re weak and small and make life worse for others. So in a sense the longing called up by Bizet and Puccini in Carmen and Butterfly is shown to be a fruitless creation of witless men, their untutored desire a path to destruction that calls into question the entire exotic mode. It is he, the French planter with French-Tonkinese children, who sings “

It is he, the French planter with French-Tonkinese children, who sings “ Blake (b. 1949) is a dyed-in-the-wool Kiwi: born in Christchurch, educated at Canterbury University, and now Chief Executive of the

Blake (b. 1949) is a dyed-in-the-wool Kiwi: born in Christchurch, educated at Canterbury University, and now Chief Executive of the  The poems are printed in full in the liner notes, and emblazoned across the album art as an epigraph is this quote from the second of them, from which Blake says the music takes its “mood of restlessness”: “Always, in these islands, meeting and parting/Shake us, making tremulous the salt-rimmed air.”

The poems are printed in full in the liner notes, and emblazoned across the album art as an epigraph is this quote from the second of them, from which Blake says the music takes its “mood of restlessness”: “Always, in these islands, meeting and parting/Shake us, making tremulous the salt-rimmed air.” The recent thought-provoking volume The Sea in the British Musical Imagination, edited by

The recent thought-provoking volume The Sea in the British Musical Imagination, edited by  When a descending trumpet figure cuts through the hymn texture, at first it feels like a response to Charles Ives’s Unanswered Question, in which the strings’ slow-moving hymn is cut through by the questioning trumpet. But there’s more to Blake’s trumpet than a dissonant question; as other instruments take up the figure, it reveals itself not as a human but as avian. To wit, the call of the

When a descending trumpet figure cuts through the hymn texture, at first it feels like a response to Charles Ives’s Unanswered Question, in which the strings’ slow-moving hymn is cut through by the questioning trumpet. But there’s more to Blake’s trumpet than a dissonant question; as other instruments take up the figure, it reveals itself not as a human but as avian. To wit, the call of the  The second, while fulfilling its memorial function admirably, also references a special kind of twentieth-century orchestral writing that I think owes a considerable debt to nature documentaries. The final work on the album is also the most recent: The Furnace of Pihanga (1999), inspired by a Maori story about the contest of mountain gods “for the love of the beautiful Pihanga.” There’s a sensitive timbral imagination on display here, and it’s a pleasure to hear Blake tell the story described in his liner notes through the orchestral medium.

The second, while fulfilling its memorial function admirably, also references a special kind of twentieth-century orchestral writing that I think owes a considerable debt to nature documentaries. The final work on the album is also the most recent: The Furnace of Pihanga (1999), inspired by a Maori story about the contest of mountain gods “for the love of the beautiful Pihanga.” There’s a sensitive timbral imagination on display here, and it’s a pleasure to hear Blake tell the story described in his liner notes through the orchestral medium. I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven.

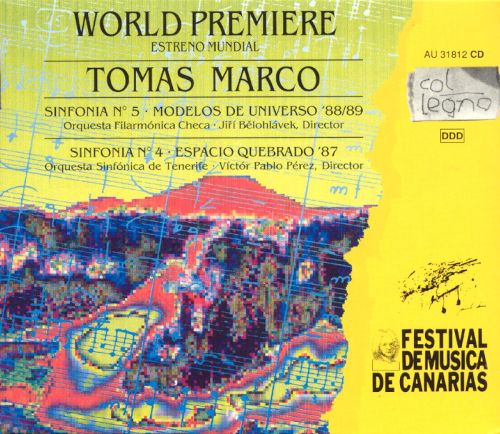

I happen to think—and I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who does—that the symphony is one of the ¡gReAt IdEaS oF hUmAnKiNd!, in the way that Peter Watson places the invention of opera between chapters called “Capitalism, Humanism, Individualism” and “The Mental Horizon of Christopher Columbus.” <1> And so hearing Brahms Second at the end of a long day was my own little piece of heaven. Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between

Marco’s Fifth Symphony has seven movements, each of which is named after one of the seven main Canary Islands: I. Achinech (Tenerife), II. Ferro (Hierro), III. Avaria (La Palma), IV. Maxorata (Fuerteventura), V. Tyteroygatra (Lanzarote), VI. Amilgua (Gomera), VII. Tamarán (Gran Canaria). (As an aside, I’ll admit that one of the reasons I was drawn to the piece is because in the last few years I’ve read a fair amount about the connection between  In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

In other words, it’s difficult to hear Also sprach, especially after 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Beethoven’s Fifth and not roll your eyes. But when ironic experience is repeated so often, it loses its ironic edge, becomes instead simply an environment. That environment is a palimpsest, endlessly written over, just as Marco’s movement titles have traditional island names and parenthetical “colonized” names, just as the symphony as a genre is a model that is written over again and again. What is left is a place of depth, a place where unfathomable things have happened and are recovered only partially, through a veil of imperfect memory, Marco Polo repeatedly trying to describe the glories of Venice for a mesmerized Kublai Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.